|

|

After the Teutonic Order was weakened and forever dismantled, most of the previous realm became a territory of Poland for two centuries, but the majority of the now Protestant Baltic Germans avoided Polish rule by declaring independence. They independently ruled Latvia and most of Estonia until after Poland defeated Russia in the Livonian Wars (1558-83) and they fell under Polish rule.

This lasted until after the Great Northern War (1700-21) when Peter the Great incorporated the Baltic states into the Russian Empire, and the Baltic Germans remained under Russian control until 1918, when they became part of independent Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia. Although a minority population, wealthy Baltic Germans, because of their vast contributions to their respective rulers’ coffers, remained in control of finances, education, the church, estates and businesses throughout this entire period, and they also dominated the politics of the region.

Dorpat University was strictly German, and most of the faculty of all schools were ethnic Germans. Germans owned 42% of Estonia’s arable land, 90% of large estates in Estonia and 90% of businesses in the capital of Riga, a port city designed and built by Baltic Germans (above center). It was not until after 1918, when Latvia, Estonia, and Lithuania became independent states, that the German cultural dominance of the Baltic waned, and it had been in control for over 700 years by then. In Memel, and throughout the Baltic, the new governments created by the victors at Versailles after World War One used the opportunity to abolish the historic German power, and at least 20,000 Germans fled from the Baltic to Germany with the retreating German army. Much German-owned property was confiscated and new dictatorships in Estonia, Latvia and Lithuania eroded the time-honored German influence, banning German-language schools, institutions, and newspapers.

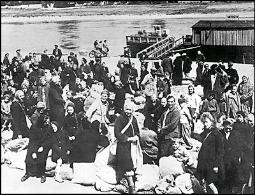

More than 60,000 total Germans left Latvia as did thousands from the other Baltic areas from 1939 until 1941. After 1945, when the Soviet Union re-conquered Latvia, Lithuania, and Estonia, the area was purged of all remaining Baltic Germans, who were either executed or shipped by train to slave camps in Siberia and Kazakhstan under deplorable conditions. Once they reached their destination, they joined over a million other expelled and enslaved ethnic German Soviet citizens, such as the Volga Germans. About 1 in 5 Germans in the Baltic died during this period.

The number of other Baltic Germans expelled are uncertain, but well over 16,000 were removed from Estonia and 62,000 from Latvia. The official German government statistics cite a total of about 256,000 German civilians forcibly removed from the Baltic, basically the entire German community. The 800-year German presence in the Baltic was extinguished.

The largest Baltic German cemeteries in Estonia, Kopli cemetery and Mõigu cemetery, both standing since 1774, were completely destroyed by the Soviet authorities. The great cemetery of Riga, largest burial ground of Baltic Germans in Latvia standing since 1773, also had the vast majority of its graves destroyed by the Soviets.

In 1939, East Prussia had 2.49 million inhabitants, 85% of them ethnic Germans with the remainder describing themselves as culturally German. Areas such as Memel, Tilsit and the Masurian Lakes region each had a proud and unique culture. Although today these historically German areas have had their histories rewritten and their native cultures erased, their real histories are more interesting.

Whole East Prussian villages had become deserted in the terrible plagues of the Middle Ages and over 30,000 people from the Memel area alone had perished. In some areas around Tilsit, not one soul had survived. The land was devastated by famine and the landscape bleak from years of decay. In 1720, the King of Prussia attempted to repopulate it and he published an immigration patent which drew in Swiss Mennonites and settlers from Pfalz, the Rhineland, Franconia, Swabia, Nassau, as well as some Dutch, Swiss, Bohemians, French Huguenots and even a group of Scots who settled around Danzig and Elbing. Later, over 20,000 religious refugees from Salzburg found new, welcoming homes in these lands. The Historian Lucanus stated in 1748: “In no European landscape was a greater mix of so many foreign nations.” These groups formed a unique culture.

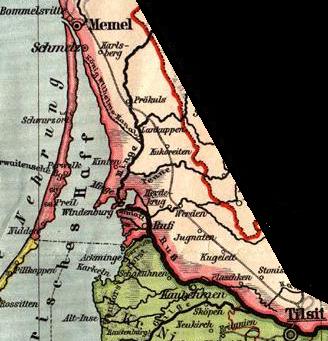

The name “Memel” can be found in sources from the 13th century. It remained the name of the city near the lower reaches of the Neman River in the former East Prussia from 1252 until 1945, with the exception of the 16 years from 1923 to 1938. The Bishop of Courland founded the Castle Memelburg in 1252, and by 1258 the town was granted Lübeck City Rights. In 1422, the border was permanently set between the Teutonic Order and the Grand Duchy of Lithuania, with Memel remaining part of Prussia. It was an important trading center during the Middle Ages and was part of the Hanseatic League

It had a long and lively trade in wood products which lasted 100 years. It became temporary capital of Prussia during the Napoleonic Wars, and from 1807 to 1808 was the home of King Friedrich Wilhelm III, his wife, his court and government. It is here, in 1807, where the king signed the October Edict, abolishing serfdom in Prussia. Memel became the most northeasterly city of the German Empire, and while the city itself was predominantly German, a third of the people of the outer region spoke Lithuanian. At end of World War I, the Treaty of Versailles severed Memel and the surrounding district from Germany without a plebiscite or input from its inhabitants because of pressure from Lithuanian representatives to the Paris Peace Conference. Memel’s population was then 80% German.

An Allied commission recommended establishing a “Free City” under League of Nations supervision in the fall of 1922. Memel’s German and Polish communities favored the proposal but local Lithuanians responded by forming a “Committee for the Salvation of Lithuania Minor.” The same American interests that created anti-German propaganda in World War One continued actively instigating in Lithuania throughout World War One and even after. An uprising began in January, 1923 against the French, and Memel Lithuanians were supported by troops from Lithuania proper. They gained control over the entire region in a week and forced withdrawal of the French garrison. The move drew “sharp,” but disingenuous diplomatic protests, and within a month the Allied Council of Ambassadors accepted it. The French left after the Lithuanian occupation was encouraged under the command of Colonel Budrys in 1923 (the Klaipėda Revolt). By 1925, the city of Memel itself was still German, but the surrounding territory had grown from one third to one half Lithuanian as new settlers were encouraged to the area by nationalistic Lithuanians.

The German community, having roots going back hundreds of years, remained unreconciled throughout the short decade and a half of Lithuanian rule. Martial law was imposed in 1926 and again in 1938. In 1939, Germany demanded Lithuania transfer the town back to its rightful inhabitants, along with the rest. Alas, the tide turn at war’s end. While some German civilians were evacuated to the west, the city was captured by the Red Army on January 28, 1945 and the remaining Germans were killed or expelled forever. German businesses, homes and properties were all stolen and the German heritage of Memel purged. All of the over 64,024 Germans in Memel were expelled. War-battered Memel was incorporated into the “proud Lithuanian” Soviet Socialist Republic in 1947, and the Soviets transformed “Klaipėda” with huge shipyards and dockyards.

Karma: Religion and even “proud Lithuanian culture” was now restricted. By 1990, there were 203,000 people in “Klaipėda,” mostly from Russia, Belarus, Ukraine, and other parts of Lithuania.

Many species are migratory. They eat insects, rodents, mice, frogs, fish and earth-worms. With their wide wing spans, storks inspired the German design of experimental 19th century gliders. Their big nests are often used for many years. They tend to be as attached to their nests as they are to their as partners. Usually monogamous, their faithfulness contributed to their stature in the mythology of various cultures.

The legend about White Storks bringing babies started in northern Germany in pagan times when people had a desire for large families and encouraged the birds to nest on their roofs to bring fertility to the home. Ironically, in early spring, if storks expect a dry summer, they sometimes throw some of their young out of the nest so there is enough food for the others.

During the 19th and 20th centuries, storks began to leave western Europe. East Prussia was the favorite home of the White Stork. There was no other country with more storks, and data on storks was diligently collected by dedicated stork lovers in East Prussia since the beginning of the 20th century when they were lovingly banded and faithfully tracked. The population of counted storks in East Prussia was 9,035 in 1934. There are far fewer numbers today.

At the end of World War Two, while northern East Prussia was given to Russia as part of the “Kalingrad Oblast,” Churchill, Roosevelt and Stalin again rewrote history and gave the lakes region of East Prussia solely to Poland as the “Warminsko-Mazurskie Voivodship.” Poles were trucked in from other regions to settled there and given the expelled Germans’ farms and houses. The international legal status of the stolen territories was still uncertain at the end of the war and there was room for differing interpretations even after the Potsdam Agreement. Therefore, any remaining German population and the centuries of evidence of a German culture and presence which identified the area given to Poland as German (rather than the “ancient Polish territory” pedaled by the propagandists) had to be quickly erased. The communist Polish administration set up a “Ministry for the Recovered Territories” with a “Bureau for Repatriation” to supervise and organize the expulsions and resettlements in former Prussia, Pomerania, East Prussia and Silesia.

All German place names were replaced with Polish or medieval Slavic ones. If no Slavic name existed, then either the German name was translated or Polish assigned. The German language was banned and there was a momentous campaign to demolish German monuments, plough under grave stones and even strip houses and buildings of distinguishable Germanic elements. Objects of German art were intentionally scattered. Protestant churches were either converted into Catholic ones or put to other use. Meanwhile, to inspire solidarity in the movement of cultural erasure, a policy which continued until 1990, the Polish government continued to spread anti-German propaganda. All past or present German property was declared formally “abandoned” as of May of 1945 and became state property in March, 1946.