On March 28, 1945, a Wednesday in the Holy Week during the dying days of the war, at a time when Germany was basically defenseless, Olpe and Attendorn were heavily bombed in a major American attack to assist the Soviet offensive. 46 American Mitchell and Boston bombers dropped 309, or 32,000 pounds of high-explosive bombs on Olpe’s residential and commercial district and on Attendom from a height from 4,300 to 3,600 meters. The whistling of falling carpet bombs drowned out the shrill warning sirens in Olpe. Crowds of frightened people frantically sought shelter from the waves of bombers, but 119 civilians died, with 80 foreign workers/prisoners adding more to the death rate. In addition, 75 people were seriously injured. 215 dwellings were destroyed in Olpe and 42 in Attendorn, with hundreds more in severe disrepair.

The majority of the death in Attendom took place in the Bahnhofstrasse, where women and girls were standing in line to shop with their Easter special food allocations. They were literally mowed down by the bombs in the surprise attack. Official findings said 150 people were killed immediately or soon succumbed to their injuries. Seven were missing.

A survivor’s accountWhen war was over, Attendorn had another terrible, terrible misfortune. At the time there was a part of the town hall in which the food office was located where many people went to pick up their food ration cards. In the basement was a large ammunition dump where, on the orders of the occupying Americans, bombs, grenades and other military equipment was collected and stored. At 10:30am on June 15, an Allied soldier with a lighted cigarette went down into the basement and shortly after, a large part of the town hall blew up. The huge explosion claimed 35 more lives.

|

|

Osnabrückers were influenced to join the Reformation, and this resulted in conflict with the Catholic bishops until the 17th century. Negotiations here at the Friedenssaal following the Thirty Years’ War led to the Peace of Westphalia, and when the Catholic and the Protestant delegations refused to negotiate in person, the Catholics were seated in Munster, and the Protestants in Osnabrück. For the city, it was compromised that it would be governed alternately by a Roman Catholic and a Protestant bishop, with the Protestant bishops being nominated by the Dukes of Braunschweig-Luneberg, and this led to the last Prince-bishop, Friedrich, Duke of York and Albany, 1763-1827, being elected at the age of 196 days old to enable him to hold the position for as long as possible. After secularization following the dissolution of the Holy Roman Empire, the Bishopric was appropriated into the Kingdom of Hannover in 1803, as confirmed by the Congress of Vienna in 1815, and then became part of Prussia in 1866. Britain’s King George I was born here, as was Erich Remarque.

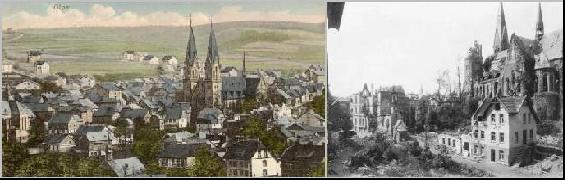

Like most German cities, Osnabrück was all but destroyed by Allied bombing in the Second World War. The flight paths of both the British and American bombers from London to Berlin and Central Germany were directly over Osnabrück. Thus, on their return flights they casually dumped their leftover bombs on the city, not for any military significance, but merely for its use as their trash can. Osnabrück was among the first and the last bombed German cities. On September 4, 1939, sirens howled in Osnabrück for the first time, the first of 2,400 trips to shelters and cellars for Osnabrückers during the course of the war (Germany did not attack Coventry until 1940).

78 air raids later, and Osnabrück was no more. The last bombing took place on March 25, 1945. 181 aerial mines, nearly 25,000 high explosives bombs, over 650,000 incendiary bombs and nearly 12,000 liquid incendiary bombs were dumped between 1942 and 1945 over Osnabrück. The bombing killed a couple thousand people, including 268 Allied prisoners of war, and injured 2,000. 750 major and 3,600 smaller fires incinerated the city. The old part of town was 85% destroyed. 14,000 dwellings were destroyed, leaving 87,000 humans shelterless. All industrial and public plants such as post offices and all public utilities were trashed. 141 public buildings, 7 churches, 13 schools and a hospital went up in flames. 900,000 cubic meters of rubble was left.

|

When an unexpected American air raid directed its fury at the small Saxon town of Ottbergen on February 22, 1945, it only destroyed a few houses, but many people fled in panic to a town shelter to find protection. This being calculated, the shelter was suddenly bombed, killing the 91 civilians who had fled there for safety. The principal target of this attack was purportedly defense cannons at a nearby plant, but they were left largely undamaged. Ottbergen would lose 79 more of its people before war’s end. |

Paderborn was an important trading town and became a member of the Hanseatic League in 1295. The city was badly damaged during the Thirty Years’ War, but rebounded and was later adorned with lovely baroque architecture. Paderborn became part of Prussia in the 19th century and linked in with the German railway.

Paderborn belongs to the list of the most destroyed cities in Germany. Only burned out ruins and mountains of rubble remained of the medieval city center after March 27, 1945, when 275 heavy British bombers accompanied by 115 American fighters set their sites on Paderborn.

The order read: ‘Destruction of city center.’ 1,200 years of history turned to ashes in a mere thirty minutes under the hellish bombardment of 200 aerial mines, 11,000 high-explosive bombs and more than 92,000 incendiary bombs. The target was supposedly the railroads, but they had already been hit. The old city center was an instant apocalypse, the large churches, including the 11th century cathedral, were lost in a sea of flame. The splendid 1613 Rathaus toppled into cinders. Thousands of rare books and irreplaceable manuscripts were lost forever both by the bombing and by the looting afterward. 85% of Paderborn was destroyed on Palm Sunday. Hundreds were killed. Later, the ruins of one of Charlemagne’s palaces was discovered beneath rubble.

|

1643 |

The long winter months and abundance of wood gave birth to a huge industry in the Black Forest, and by 1808 there were already 688 clock makers and 582 clock peddlers in this neck of the forest. Clock peddlers would peddle the gaily painted and embellished clocks in summer.

Pforzheim is one of the smallest towns in Baden, and would not even be memorable, had it not been for its ruin. Located at the confluence of the Wurm, Enz and Nagold Rivers at the northern rim of the eastern part of the Black Forest, the “Pforte zum Schwarzwald” or “Gateway to the Black Forest” once held a Roman settlement.

A ford was built here through the river for the Roman military highway. Pforzheim later on became a center for timber rafting from the Black Forest via the rivers Nagold, Enz and Wuerm, and then the Necker and Rhine to far away lands for use in shipbuilding. It was an important medieval trade center, often changing hands until it passed to the Margraves of Baden in the 13th century, and it served as their residence until 1565.

Pforzheim was damaged in the Thirty Years’ War and devastated by the French in the War of the Grand Alliance in 1689. But, the little city rebounded and maintained life as a quiet hamlet on the edge of the Black Forest. It was called the “Paris of the Black Forest” because of its medieval charm, and the “City of Gold” because of its jewelry and clockmaking.

The post-war British Bombing Survey Unit called the gruesome bombing destruction of Pforzheim, which was based on a rumor, “probably the greatest proportion in one raid during the war.” It was a “smashing” success.

American eye-witness account: “The Group Headquarters entered Pirmasens late the night of the 23rd and here at close range saw the devastating effects of Allied aerial bombing. The town of perhaps fifty thousand was practically leveled. German families were huddled together wherever they could find shelter. Others wandered in a daze through still smoking rubble Broken water mains spouted water and the smell of death was everywhere. That night the Group found a place to bivouac near a mausoleum and cemetery at the edge of town. In back of the buildings were row upon row of coffins of the unburied dead and within the mausoleum was a large room completely filled with corpses. We were glad to soon move on. The following day the results of Allied air power could be seen again along a mountain road. For well over a mile were at least two hundred dead horses from a German supply column that had been strafed, still harnessed to their wrecked wagons. I for one was not ashamed to feel the same deep sorrow and anguish that I had felt on seeing our dead GIs, and for that matter the young teen age dead German soldiers.”

There was once a rich cotton dealer, Baumgärtel, whose stuccoed festive hall dated from 1786. He was a Schleierherren or veil man of Plauen, and sold woven fashion merchandise in the 18th century. Plauen lace became famous throughout the world after 1880. The Lutheran church at the northern edge of the old city had existed since 1722, and was the oldest significant Baroque building left in Saxony. Its four-winged altar, which was in the St. Thomas Church of Leipzig until 1722, was created around 1500 near Erfurt.

5,700 tons of weapons were dropped by British and American bombers on Plauen, destroying 75% of the city and killing 2,443 humans in 14 air raids. In the bombing, the citizens had ingeniously fortified old rock cellar areas under a former factory. The underground halls held 7,000 to 8,000 persons and it had its own water and electric supply. However, in these closed cellars crowded with people, the air supply became dangerous during 2-3 hour air raids. Ancient St Johann’s Church was all but totally destroyed. From April 16 to June 30, 1945, the American army occupied Plauen and the Vogtland, containing the people before handing them over to the communists on July 1. The ancient city entrances were later blown up by Soviets.