The militia then pursued the enemy troops through the Wipp Valley, inflicting casualties. The French occupied Innsbruck, but left only a small garrison of troops there. Under Hofer’s inspirational command, patriots from all over the province swelled his troops and readied for battle. Victory was theirs, Hofer’s famous motto in their heads, “You’ve been to mass; you’ve had a schnapps. Now forward in the name of God!” This resulted in the temporary reoccupation of Innsbruck by the Austrians. On the morning after, extremely religious Hofer called all his officers together on the hill for prayer and then proclaimed himself governor of the province in the name of the emperor himself, and for two months, while the Tirol was free from invasion, he ruled the country and lived like a simple peasant.

Hofer thought he could return to his home and leave the government in the hands of an attendant who had been sent from Vienna. However, the Tirol was abandoned at the armistice of Znaim, and French Marshal Lefebvre advanced to subdue the country. Hofer inspired the people to risk their lives for faith and freedom, and they organized resistance to the French “atheists and freemasons.” On August 13, in another battle on the Iselberg, the French were routed by the Tirolese peasants under Hofer. The Bavarians were again forced to evacuate the country, and Hofer entered Innsbruck in triumph with the government in his hands. He moved into the Hofburg, and ruled his countrymen.

Francis II bestowed on him a golden medal, which led Hofer to innocently believe that the emperor would never abandon his faithful Tirolese. However, news of the conclusion of the treaty of Schönbrunn, by which Tirol was again ceded to Bavaria, reached him on October 14, and he was shocked. On November 1, he lost the third battle of Berg Isel against a superior force of the enemy and Hofer was forced to flee, with a hefty French reward on his head.

The overpowering French force pushed into the country at once, and because an amnesty had been stipulated in the treaty, Hofer and his companions, after some hesitation, caved in. On November 12, however, after discovering deceptive reports of Austrian victories, Hofer changed his mind and decided to fight to the last, again issuing a proclamation calling the mountaineers to arms.

He met little response. Hofer, a bounty on his head, had to take refuge in a mountain hut on the Pfandler Alm with a faithful follower Kajetan Sweth, remaining there from November. A greedy countryman, Josef Raffl, betrayed him for the reward, and on January 27, 1810, Hofer was captured by Italians and sent in chains to Mantua. After a hasty hearing, and without even waiting for the sentence, he was shot to death in Mantua on February 20, 1810. This act caused immense disgust all over Germany.

It also inflamed more hatred of the aggressive French. Just hours before his death, Hofer wrote to a friend: “Goodbye cruel world. Death comes so easily to me that there will be no tears in my eyes.” Shortly before he died, he said: “The Tirol will again be Austrian” and in three years it was. In 1823, Hofer’s remains were removed from Mantua to Innsbruck, where they were interred in the Franciscan church, and in 1834, a marble statue was erected over his tomb.

In 1893, a bronze statue of him was also set up on the Iselberg. In 1818, the patent of nobility bestowed upon him by the Austrian emperor in 1809 was conferred upon his family.

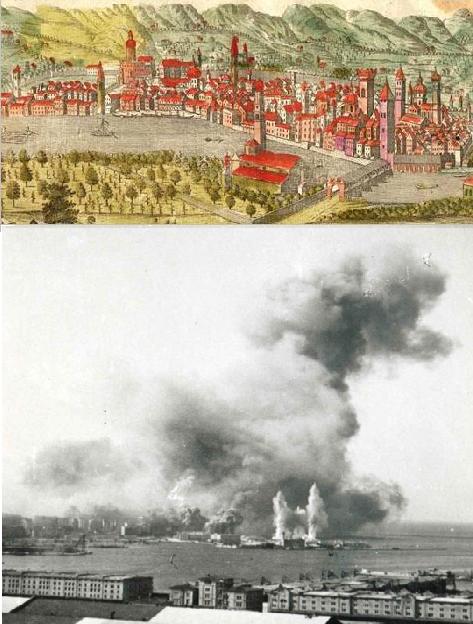

The Tirol line of the Habsburgs died out in 1665, but Maria Theresa helped the city retain its glory by building more fabulous buildings. Tirol was ceded to Bavaria after Napoleon’s conquest in 1805 and it remained so until 1814, when it was given back to Austria at the Congress of Vienna. After the railway came through the Brenner pass in 1884, Innsbruck became a vital, prosperous crossroads linking north and south as well as east and west.

After World War One, as part of their move to prevent any future German or Austrian power, the Allied victors at Versailles severed German-speaking South Tirol from its historic and cultural roots in Austria. At the Treaty of Saint-Germain of September 10, 1919, Italy was given the ethnic German territories south of the Alpine watershed, including the southern part of the Austro-Hungarian County of Tirol. Some 150,000-200,000 Tirolese German citizens were therefore sacrificed to Italy to do with as she saw fit. At the time of the annexation in 1919, the overwhelming majority of the people were of German heritage and spoke German.

Italy formally annexed the territories on October 10, 1920 and one of the first orders of the Italian military regime was to seal the border between South Tirol and Austria, the people forbidden to cross the new frontier. This move tore family, friends, businesses and even church parishes in two. The postal service and traditional trade were interrupted and censorship was introduced. On May 15, 1921 the Italian government, although retaining military and police control of the newly created provincial council of the “Provincia di Venezia Tridentina,” did allow the first free democratic elections (the last the people would see until April 18, 1948!). The result was a resounding victory for the Deutscher Verband (German Association), which won close to 90% of the votes and thus sent 4 deputies to Rome. The German-speaking population was largely able to go about their normal business as usual during this short time, however.

However, on Sunday April 24, 1921, as the German population of Bozen participated in a traditional parade honoring spring events, 280 out-of-province Italian fascists arrived by train and, joining forces with 120 local fascists, proceeded to attack the procession with clubs, guns and grenades, injuring 50 people and killing a local artist. Nobody was ever brought to justice for the attack. This was an omen of worse things to come. In October 1922, the Italian government rescinded all protection of linguistic minorities and began an Italianization program which demanded the exclusive use of Italian language in the public offices and the closure of most German schools. It also offered incentives for immigrants from other Italian regions to relocate with the intention of diluting the German majority, and with this goal in mind, a large industrial zone was soon opened in Bolzano to lure workers and their families to the area from other parts of Italy. Public service jobs became an exclusive domain of Italian speakers. As in other areas where the Allies artificially created new populations, the Italian-speaking population grew from 3% in 1910 to over 34%. There would be trouble in days to come.

With the vengeful Allied separation of South Tyrol from Austria, there was a painful tear in history at the Schneeburg mountain mining community. With each departing or torn-apart miner family, the close bond which had developed over the centuries disappeared along with historical uniforms, language, holidays, customs, music, privileges and area names. Their various connections to the surrounding valleys and the divided Tirol disappeared or were interrupted by the closed state border.

In 1939, the German-speaking population was given a terrible choice of either emigrating to neighboring Germany/Austria or staying in Italy and accepting complete Italianization.

During the Second World War, the Austrian Tirol suffered massive damage from air attacks. In a bomb attack on small Woergl, February 22, 1945, 69 civilians were murdered, 43 houses destroyed and 105 badly damaged. From 1943 until April, 1945, Innsbruck experienced 21 bomb attacks and suffered heavy damage. By May 1945, Innsbruck lost hundreds of civilians to the Allied terror-bombing. The Innsbruck cathedral, with its domes and Baroque interior featuring a high altar painting by Lucas Cranach the Elder, the Bahnhof and Maria-Theresienstrasse were destroyed. The Cathedral has since been rebuilt. 20,000 tons of bombs were dropped on Vorarlberg and north and South Tirol, killing 1500 civilians. Over 6,849 sorties were flown over targets from Verona to the Brenner Pass with 10,267 tons of bombs dropped on cities such as Trent (Trient, Trento).

The city of Trent (Trient, Trento) is on the river track to Bolzano and the low Alpine passes of Brenner and the Reschen Passes over the Alps. In 1027, Emperor Conrad II created the Prince-Bishops of Trent, who wielded both temporal and religious powers. In the following centuries, the sovereignty was divided between the Bishopric of Trent and the County of Tirol (from 1363 part of the Habsburg monarchy). Trent became an important mining center.

Trent became famous for the Council of Trent (1545–1563) which gave rise to the Counter-Reformation. The prince-bishops ruled Trent until the Napoleonic era, when it bounced around among various states. Under the reorganization of the Holy Roman Empire in 1802, the Bishopric was secularized and annexed to the Habsburg territories. The Treaty of Pressburg in 1805 ceded Trent to Bavaria, and the Treaty of Schönbrunn four years later gave it to Napoleon’s Kingdom of Italy. With Napoleon’s defeat in 1814, Trent was finally annexed by the Habsburg Empire, becoming part of the province of Tirol.

After World War One, Trent, along with Bolzano (Bozen) and the German-speaking part of Tirol that stretched south of the Alpine watershed, were annexed by Italy, but then annexed to Greater Germany in 1943.

From November 1944 to April 1945, Trent was bombed as part of the so-called “Battle of the Brenner.” War supplies from Germany to support the Gothic Line were for the most part routed through the rail line through the Brenner pass. As stated, over 6,849 Allied sorties were flown over targets from Verona to the Brenner Pass with 10,267 tons of bombs dropped on Tirol cities and towns. Parts of Trent hit by the Allied bombings included the Renaissance church of S. Maria Maggiore, the Church of the Annunciation and several historic bridges over the Adige river.

Daily food rations were below 1,000 calories. Life was grim for Tirol’s residents. As the Allies had decided that the province should remain a part of Italy, Italy and Austria negotiated an agreement in 1946, recognizing the rights of the German minority. This lead to the creation of the region called “Trentino-Alto Adige/Tiroler Etschland” by the new name of “Venezia Tridentina.” German and Italian were both made official languages, and German-language education was permitted once more. But as the Italians were the majority in the region, the self-government of the German minority had become an impossibility. The French occupied Nord-tirol until 1955. East Tirol was occupied by the British until 1953.

More and more Italian-speaking immigrants were enticed to the area, leading to strong dissatisfaction among German South Tiroleans, which culminated in acute tension and violence, and the South Tirolean question (Südtirolfrage) became an international issue which was taken up by the United Nations in 1960. Eventually, the area of Bolzano-Bozen gained new autonomous status from 1972 onwards which has resulted in a considerable level of self-government and South Tirol today is one of the wealthiest Italian provinces and enjoys a high degree of autonomy. It has strong relations with the Austrian state of Tirol.

As a result of Italianization, only about 69.15% of today’s South Tirol population are German-speaking and 25% are Italian-speaking (35% in the 1960s). Some ethnic tensions still persist. Italians no longer have a monopoly on public service and government jobs and the independence controversy is an especially keen issue of the German parties and the idea of a Freistaat (free state) has surface again and again and there are strong advocates of self-determination. In Hofer’s words, Tirol might once again be Austrian.