The war on German culture began with vicious assaults on the German language which was the mother tongue to more than nine million Americans when Wilson signed the first bill restricting the German press on October 6, 1917. At this time, there were German language book publishers in nearly every major American city, each producing thousands of German books and school texts yearly, and there were many thousands of German-language magazines and newspapers in the US. Their days were numbered. The Atlantic Monthly was one of the first major publications to accuse the German American press of mass disloyalty, and the others soon followed. The New York Times stated that German newspapers “never stopped trying to surreptitiously support Berlin’s cause.” The Saturday Evening Post went a step farther and declared that it was time for America to rid itself of Germans, the “the scum of the melting pot.”

In 1917, Minnesota’s German-Americans formed the state’s largest ethnic group with 70 percent of the state’s residents either immigrants or first-generation Americans. Minnesota’s seven member “Commission on Public Safety,” formed by the state with its members appointed by Governor Burnquist, even requested a state firing squad for ‘slackers.’ Having no public accountability, the clan of business leaders with personal financial interests in an Allied victory immediately suspended civil rights, set up an armed militia and created a network of spies, all with the CPI’s blessing and guidance. It soon became among the harshest organizations in the country.

Three elected New Ulm officials were accused of lacking patriotism because, while they supported the draft, they suggested that German-Americans serve in non-combatant capacities since they might be killing relatives. They were suspended on grounds of disloyalty.

Military leaders and federal officials, including Wilson, considered suspending constitutional rights and freedoms nationally to counter opposition to the war and censoring the press to block accounts of wartime problems. This was tricky, so Creel, as the country’s first propaganda minister, instead used his “persuasive” method of working with groups such as Minnesota’s Commission on Public Safety to do the dirty work for them. In that vein, in 1917, the figure of Germania was torn from the Germania Life Insurance Building in St. Paul, Minnesota and the building renamed. Minnesota not only followed the lead in other states of banning any language but English, it created mini-militias, demanded loyalty oaths and required grueling alien registration.

Wisconsin also had a huge German American population in the War years, as well as politically dominant Progressive and Socialist figures who opposed the war, such as Senator Robert La Follette. Participation in the war was a contentious issue in 1917, and when the U.S. officially entered the war on April 6, 1917, nine of Wisconsin’s eleven Congressmen plus Senator La Follette voted against the declaration of war. LaFollette faced constant degradation, ridicule and slander.

For a time, and against all odds, Wisconsin’s German American community maintained many organizations devoted to preserving their heritage and they had a strong cultural unity because of the vigorous German language press and their joint stand against prohibition. Milwaukee Socialists were another voice of anti-war sentiment. Before the US involvement in the War, Milwaukee’s German community was almost entirely pro-Axis. 170,000 Milwaukee German Americans turned out at a charity bazaar in 1916 and raised $150,000 for German war relief. Wisconsin was nicknamed the “Kaiser’s state” during this period.

The majority of Wisconsin citizens did not oppose the war for long, however, after the government cleverly saw to it that their businesses, workers and especially farmers were financially rewarded from war contracts. Even the Socialist mayor of Milwaukee finally caved in to the war fever and participated in preparedness parades, cooperated with the draft and established a Milwaukee council of defense at the same time that he defended the rights of opposition. The sell-out was at a hefty price: 118,000 of their citizens were sent into military service and many of their boys died.

Wisconsin was the first state to organize a State Council of Defense as well as County Councils of Defense. These organizations helped to “educate citizens on the war and the sacrifices that were demanded of them.” The Wisconsin “Loyalty Legion” soon set to work eliminating all things German. It first succeeded in having the description of Milwaukee as the “German Athens” removed from state guidebooks. Then it cajoled residents in Green Bay to rip down and smash a statue of Germania, which they deemed a “symbol of German Kultur” from a city office building. Only after destroying it did they realize they had not smashed Germania, but the Goddess of Liberty! They also draped cloaks over the Schiller and Goethe Memorial statue in Milwaukee’s Washigton Park for the duration of war.. only because they were refused permission to destroy it.

The 8-story, 90,000 square foot Germania Building was designed by German-trained architects and built in 1896 for George Brumder to house his German American publishing empire. It had copper “pickelhaube” domes and was graced by a 10-foot-tall, three-ton bronze statue of Germania over its door. Alas, in 1918, one “Lieutenant A. J. Crozier” of the British and Canadian recruiting office in Milwaukee led a mean-spirited campaign to rid the building of its statue, and when it was removed discretely in the night, he snidely quipped that he hoped it would be melted into bullets to kill Germans with. He also demanded the building be renamed, and Germania building became the Brumbder building. The fate of the statue remains a mystery.

In Wisconsin, almost 100 German language newspapers were being published and Milwaukee was a leading national center for large German-language publishing houses since 1844. Now, German language textbooks were burned in the streets of big cities and in small towns like Baraboo, where the Wisconsin National Guard itself started the bonfire of books on the main street on June 13, 1918.

Vigilantes set up a machine gun outside the Pabst Theater in Milwaukee to prevent the production of Schiller’s play ‘Wilhelm Tell.’ Brewery tycoon Captain Frederick Pabst built the Pabst Theater in 1895. Designed by architect Otto Strack in the tradition of the great European opera houses, the theater was nationally known for its German-language stage productions. It opened on November 9, 1895 and was home to Milwaukee’s German theater company. It was the leading theater in Milwaukee and one of the finest theaters in the US. In 1918 the Milwaukee Journal formally and publicly requested that the Pabst Theater discontinue all German language productions, which it did. The Journal also attacked its competition, the local German language newspapers, for “disloyalty” and “hatred for the American government.

Judges were not lenient when the shoe was on the German foot. German-American farmer Charles Naffz, whose son was serving in the US Army, was overheard complaining about the war being a “rich man’s war” and promptly fined 100 dollars. Henry Denger was a former postmaster and high school principal as well as an opponent of war when he was arrested for espionage because he “assaulted” a persistent hawker of liberty bonds. They weren’t all sheep. The Secretary of State of Wisconsin received a thirty-month sentence in federal prison for referring to the YMCA and the Red Cross as “a bunch of grafters.” Wisconsin citizens returned to the Progressive leadership of Robert La Follette after war’s end, and he opposed the unjust Versailles Treaty and American membership in the League of Nations, seeing the League as an organization only for victors’ benefit.

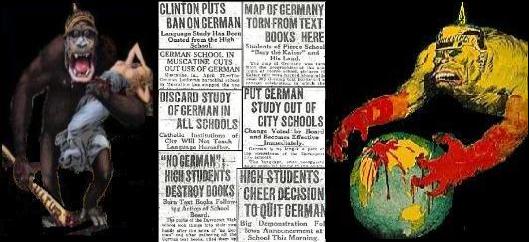

Within weeks of the war’s onset legal action was brought to eliminate the German language from schools in America. In virtually every state there were incidents, some quite violent, of criminalizing the German language, and book burnings erupted all over the USA. German-Americans were about to suffer a major culture shock, and what took place in Iowa is a prime example. Germans were the largest immigrant group in Iowa when, on November 23, 1917, the Iowa State Council of Defense demanded that all Iowa schools cease teaching German. Davenport, once labelled “the most Germany city in the Midwest” and the center of all German activities in the state, had by then already discontinued the study of German in their city schools. 1918 Davenport headlines, above with insidious German “Kultur” emblazoned on the ape’s club and German seeking world control.

On May 8, 1918, the Board of Education hosted a book burning and students from several local schools incinerated over five hundred German textbooks while singing patriotic songs. When the Davenport Public Library removed all “decidedly pro-German” (in other words, all German language) books from its shelves, the Davenport Democrat and Leader trumpeted this as an act in the “crusade to extract Kaiser Wilhelm’s poisonous ‘kultur venom’ from Iowa libraries.” Although the German vote had won him election, Iowa’s Governor William Harding issued “The Babel Proclamation” on May 23, 1918, becoming the only governor in the United States to outlaw the public use of all foreign languages. German instructors were fired and German textbooks burned.

Many German immigrants settled in the Davenport Iowa area. One tradition they brought with them was a Schuetzenverein, or shooting club. Davenport’s club was formed on August 6, 1862. Its members established a large park for shooting and social events, drawing crowds of more than 12,000 people a day. It had the works: a dance hall and music pavilion with refreshment stands, bowling, a roller coaster, a zoo, athletic and picnic grounds and even an inn. The “Schuetzenpark” was the site for concerts and saengerfests. When the park celebrated its 25th anniversary, 10,000 people showed up to hear speeches given in both English and German and to enjoy local band music. In 1899, at the urging of the Davenport Turners, an athletic field was created in one section of the park. The park was so popular that by 1911, it had its own streetcar stop.

Some members of the Schleswig-Holstein Kampfgenossen, a group of German freedom fighters who had taken part in the unsuccessful German rebellion against the Danish monarchy in 1848-50, had emigrated to Iowa. On March 24, 1898, a monument was erected at the Schuetzen Park to mark the 50th anniversary of their struggle. More than 1,200 people gathered to honor the event and watch the dedication of a stone monument and observe the planting of three oak trees, two of which were donated by Otto von Bismarck himself.

During the hysteria of 1918, the stone was painted yellow, tipped over and finally vanishing, perhaps pushed into the Mississippi River. Old Schuetzen Park was renamed “Forest Park” and the venerable Davenport Schuetzen Verein became known as “the Davenport Shooting Association.” Its popularity declined further with Prohibition. The park was sold in 1923 and today all that is left of the only original park buildings is the 1911 street car station. (the Davenport Schuetzen Verein did not perish, however, and has been carefully nurtured back to life by dedicated individuals. Also, a new monument was recently rededicated to replace the missing stone, a link in Davenport’s Germans’ heritage, thanks to some courageous citizens who are righting an old wrong).

Street names all over the state were changed. Berlin Township was reinvented as “Hughes” and Germania turned into Lakota. The statue of the goddess Germania that had stood in Davenport since 1876 was removed and sold as scrap iron. Davenport’s “German Savings Bank” was, of course, renamed. The cartoon at left captioned, “Here lies Kultur” displays the relentless effort to portray German culture as evil and murderous, and it was sadly successful, even to Germans.

In Atlantic, Iowa, a gang broke into the local high school and burned all of the German books while shouting “No more German!” on March 19, 1918. From Sioux City to tiny farm hamlets, mass burnings of German books were conducted across Iowa. All conversation in public places, on trains, over the telephone and in public addresses had to take place in English. Party line telephone conversations overheard by switchboard operators and eavesdroppers were reported to authorities. One big sting netted five Iowa farm wives who were arrested for speaking German during a party line telephone conversation. The women were fined $225 which was given to the local Red Cross.

For generations, children in Iowa’s old Amana Colony spoke German in schools and learned English only as a second language. But when the US entered the war, state investigators monitored Amana schools throughout the war to make sure Amana was “not on Germany’s side.” After the new law banned the use of any language other than English, there was a devastating effect. Although the law was overturned at the end of war, the more widespread use of English which had been forced on the Amanas could not be reversed. Kids still received Sunday school lessons in German, but English was taught in the schools, and their old German dialect was by and large lost.

The Mockett Law in Nebraska (whose legislature ignored the state’s large German population who put them in office) decreed in April of 1919: “No person, individually or as a teacher, shall, in any private, denominational, parochial or public school teach any subject to any person in any language other than the English language.” When the Missouri Synod Lutherans of Nebraska brought a test case, Meyer v. Nebraska, the ban on German was reconfirmed by all courts until it reached the U.S. Supreme Court who on June 4, 1923 declared it unconstitutional (with the old war hawk Justice Oliver Wendell Holmes dissenting). They held that a mere knowledge of German could not be regarded as harmful to the state, and added that the right of parents to have their children taught in a language other than English was within the liberties guaranteed by the Fourteenth Amendment.

By 1919, 27 states had banned instruction in and of German. Schools that didn’t burn their German books silently disposed of them, encouraged by the government to ban teaching or speaking of German. Philadelphia, Newport, Kentucky and Lafayette, Indiana all banned the teaching of German, and many other areas, including Milford, Ohio tried to ban the speaking of German. One phone company even banned the speaking of German on its telephones, and English was demanded in most courts. Libraries in Detroit, Denver, St. Louis, New York, Cleveland, Portland and Washington, D.C. all banned German books. Like Scouts in many other cities, Columbus, Ohio’s Boy Scouts burned local German-language newspapers.

Heavily Germanic Cincinnati, Ohio published more than 30 German language publications before all German-language books were banned from the public library. Thousands were destroyed and all German language classes were dropped from the school system.

In 1850, 31,000 of the Cincinnati Ohio’s 115,000 citizens were German-born, concentrated mainly in the Over-the-Rhine district; By 1890, over half of Cincinnati’s 300,000 residents were German-American, and there were clubs, singing societies, a German theater, a myriad of newspapers and journals, 48 German churches, 2 orphanages, homes for old men and women, six cemeteries and many banks. Yet, anti-German sentiment had a drastic effect which even enveloped the Queen city of Teutons. German-American citizens and businesses quickly changed their names under pressure. German National Bank became Lincoln National Bank. Even traditional German Celebration Day was canceled in 1917. German Life Insurance Company in Cincinnati hid the figure of Germania under a flag until it was changed to a figure of Columbia.

Cincinnati began changing street names in 1918: German Street became English Street, Bismark Street turned into Montreal Street, Berlin Street to Woodrow Street, Bremen Street to Republic Street, Brunswick Street to Edgecliff Point, Frankfort Street to Connecticut Avenue, Hanover Street to Yukon Street, Hapsburg Street to Merrimac Street, Schumann Street to Meredith Street, Vienna Street to Panama Street, Humboldt Street to Taft Road and Hamburg Street to Stonewall Street.

By 1900, Cleveland was 4th behind Milwaukee, Hoboken and Cincinnati in German population and 2 out of 5 Clevelanders were German. In 1902, there were over 200 German-American clubs and organizations, many newspapers, churches and schools. Germans were jewelers, tailors, machinists, cabinet makers and brewers. Germans built hospitals, schools and institutions of higher learning. This is one resistant city that amazingly experienced not much in the way of repercussions from the hysteria, although members of the Cleveland YMCA covered the name “German” in the German Hospital’s sign with an American flag, arguing that “the very word affected (their) appetites.” New Berlin, Ohio changed its name to North Canton to show its patriotism. Better Chinese than German.

Indianapolis, Indiana had a huge German population as well, and it kept growing. They had clubs, newspaper, music and singing societies, and public schools offered German language classes. Germans ultimately had a greater influence on Indianapolis than any other immigrant group. Das Deutsche Haus was a beautiful old European-style building where Germans gathered and socialized. During the war, its Germanic heritage unraveling, the Deutsche Haus became the “Athenaeum.”

Like many American cities in the late 19th century, Germans made up more than one third of the total population of Buffalo, New York. Five of the city’s banks were capitalized with German investment. There were 25 German breweries, 6 German insurance companies, a German hospital, scores of German churches, several turnvereins and the famous Saengerbund Singing Society. Numerous businesses and stores were owned by German Americans. German doctors and lawyers were among the most successful in the city and German politicians among the wealthiest and most powerful people. By 1900, the Germans made up more than half of the city’s population, but anti-German feeling during the War lessened the city’s increasingly German character and even led to changes in street names. Typically, the German-American bank, chartered in 1882, changed its name to the Liberty Bank. Today, nobody much thinks of Buffalo as being such a “German” city. Elsewhere in New York, in 1918, the City University of New York decided to reduce by one credit every course in German.