Prior to 1897, Germany was held in very high respect by the Chinese. German monks from Frankonia had established a brewery in Tsingtao, calling their product “Tsingtao Beer,” and back in 1872, the military governor of the province of Chihli sent several Chinese military officers to Germany to attend the Kriegsakademie. When a military academy was established in 1885 near Tientsin (Tianjin), German military instructors were hired, as they were when a second military academy was opened in Canton. When Japan first defeated China in the Sino-Japanese War, the Imperial Chinese Court ordered the establishment of two new armies based on German drill instructions, German organization and German training efforts. In addition to providing military advisors, Germany also provided China with economic advisors, and in 1891, German won a contract to build a small railroad in China. Theirs was an old, mutually beneficial friendship.

The “Boxer Rebellion” which was about to develop was an uprising against foreign influence which had its roots in China’s humiliation at losing control of Korea and Formosa to Japan, and the anger felt by their elite was directed at the Europeans who were a dominant influence in China. Also known as the Righteous and Harmonious Society Movement, it began in the Shandong Province in 1899, and thousands of Chinese Christians and European missionaries were savagely murdered. In total, 222 Chinese Eastern Orthodox Christians along with 182 Protestant missionaries and 500 Chinese Protestants were murdered. 48 Catholic missionaries and 18,000 Chinese Catholics were also butchered. Even their children were mowed down mercilessly. The Imperial court of Beijing under Empress Dowager Cixi was controlled by ultra-conservatives who supported the Boxers.

In June, 1900, the Boxers and parts of the Imperial Army began attacking foreign embassies in Beijing and Tianjin. Anticipating problems, a mixed force of 435 marines from eight countries were sent to reinforce the guards at the embassies of Great Britain, the United States, France, Belgium, the Netherlands, Russia and Japan. The embassies were linked into a fortified compound as the Boxers approached, and those embassies located outside of the compound were evacuated, with the staff taking refuge inside. On June 20, the compound was surrounded and attacks began. German envoy Klemens von Ketteler was killed trying to seek refuge in another part of the city.

To deal with the Boxer threat, an alliance was formed between Austria-Hungary, France, Germany, Italy, Japan, Russia, Great Britain, and the United States which eventually numbered 54,000 troops. Field Marshal von Waldersee commanded the German contingent, and this German participation did great damage to the harmonious feelings once enjoyed between the Chinese and the Germans.The Boxers were defeated and the result was the Boxer Protocol, which required the execution of ten high-ranking leaders who had supported the rebellion, as well as payment of 450,000,000 tael of silver ($333 million) as war reparations.

After the Boxers were defeated, virtually all of the European and American troops thoroughly looted the city, carrying off items of great value and cultural significance. They broke into palaces, temples and businesses to steal porcelain, silver, jewelry, furs, silks and bronzes. Old Cathedrals were turned into warehouses for storing the plunder. One American diplomat filled several railroad cars with loot. The British Legation held daily auctions for its well-organized loot. American soldiers, although prohibited from looting, disregarded the orders. Even missionaries got into the act and prowled Chinese villages and neighborhoods for loot which could serve as “restitution” to missionaries and Chinese Christian families whose property had been destroyed. One missionary even set himself up as a mini-emporer in his province and held restitution trials.

The allies occasionally turned on each other in quarrels over dividing loot, and as French troops ravaged the countryside around Beijing to collect indemnities on behalf of Chinese Catholics, Russian soldiers were accused of ravishing the women and committing horrible atrocities in the sector of Beijing they occupied. Meanwhile, the Japanese were beheading Boxers or people they suspected of being Boxers. Contributions made by former European Jesuits in China were raided. Fourteen seventeenth-century cannons and countless other valuables were divvied up by Italy, London, Vienna and Hungary and the vast, main Jesuit scientific library was given to the Czar of Russia.

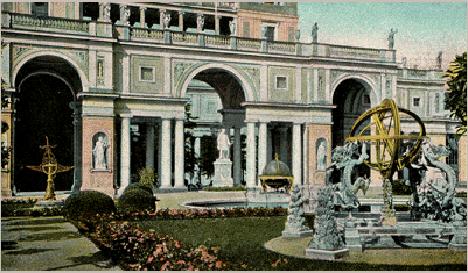

Despite the cooperative nature of this massive orgy of looting, by the onset of World War One, these shameful events were transformed by the media into “the German looting of China.” On January 6, 1918, The New York Times Magazine ran a piece titled, “Kaiser Wilhelm as a Pillager in Boxer Days.” Another contemporary article on the subject started with, “On the terrace of the Orangery in Potsdam are the Chinese astronomical instruments which Germany appropriated during the Boxer uprising, remarkable examples of Eastern bronze-casting and of Western greed.” Even today, there is little else said on the subject beyond references to the “German” looting, using words such as “stole” and “grabbed.” By the punitive terms of the Treaty of Versailles, Germany alone (the least aggressive of all the looters), was held accountable and forced to return their share of items taken from China.

This brings us to the various astronomical instruments in question which were carried away in 1901 by the Germans, items considered by them to be a fair share of their Boxer Rebellion indemnity, for they incurred considerable financial losses in China. Kaiser Wilhelm had some of the items (which were not Chinese, nor made by the Chinese, but had been built for the imperial observatory in Beijing by German Jesuits under Johann Adam Schall and Belgian Father Ferdinant Verbiest) brought to Potsdam and set up in the front yard of the orangery in Potsdam Sanssouci for all to see, among them a celestial globe used to map and identify celestial objects. Who were these men?

Johann Adam Schall von Bell, born of noble parents in Cologne, Germany, attended the Jesuit Gymnasium and joined the Society of Jesus in Rome in 1611. In 1618, he left for China and arrived in Macao in 1619 where he studied Chinese and mathematics. In 1623, he was invited to go to Beijing to assist the Chinese military since he was adept at firing canons. In 1629, after predicting the exact time of an eclipse which was to occur on June 21, he remained as court mathematician and astronomer. It is believed that he probably brought the first telescope to China in 1619 along with other instruments and his European books. He wrote numerous works and his opinions were highly valued. In 1635, he presented the last of the new calendar to the court.

Schall was given a new house and a church, the first public church opened in the capital since the coming of the missionaries and dedicated in 1650. Schall founded a new Christian congregation at Ho-Kien, capital of one of the prefectures. During Schall’s time, there was a rapid increase in the number of neophytes; in 1617 they were 13,000; in 1650, 150,000, and from 1650 to the end of 1664 they had grown to at least 254,980. His position enabled him to procure from the emperor permission for the Jesuits to build churches and to preach throughout the country. 500,000 are said to have been baptized by Jesuit missionaries within fourteen years.

The Emperor of the Ming Dynasty was overthrown when the Manchu tribes established the Qing Dynasty, and in 1645, the new government asked Schall von Bell to develop a new calendar. Schall participated in compiling and modifying the Chinese calendar then known as Chongzhen Calendar, named after the last emperor of the Ming Dynasty. The modified calendar provided more accurate predictions of eclipses of the sun and the moon.

Emperor Shun-chi died in 1662, and the child who was proclaimed his successor became the famous K’ang-hi who was favorable toward the Christians, but some regents in his government were not. They manipulated the imperial court into bringing charges against the Jesuits for high treason and teaching false mathematics, astronomy and religion, and sentenced them, along with their Chinese aides, to death in November, 1664. Luckily for the victims, on the morning that they were to die, an earthquake hit Beijing and part of the Imperial Palace was destroyed. This was taken as an omen and Jesuits were freed, although their Chinese assistants were executed.

Schall von Bell died soon afterward, after spending 47 years in China, on August 15, 1666 at the age of 75. According to one story, Schall was said to have spent his last years in the house given him by the emperor with a woman who acted as his wife and who bore him two children, but it has never been proven. Following his death, the Kangxi Emperor restored his honors, purged Yang Kuang, and eventually appointed Belgian Ferdinand Verbiest as head of the observatory in 1669 and bid him to create another new calendar.

Like his predecessors, Verbiest studied Chinese and taught the Kangxi Emperor. For his work on the calendar, he needed new instruments to introduce a new scale to Chinese measurement. Working on designs based on those of Tycho Brahe, he created six instruments: the ecliptic armillary sphere, the equatorial armillary sphere, the azimuth, the quadrant, the sextant, and the stellar globe which Chinese bronze casters fabricated. Verbiest contributed much to cartography as well and wrote over 30 books. He cast canons and, as part of his interest in hydraulics, invented a working “automobile” by placing a steam pump on wheels.