Its diverse population represented the many German states and their inhabitants who, with their regional dress, customs and dialects, still thought of themselves as Bavarians, Prussians, or Saxons rather than as ‘Germans,’ even after German unification in 1871. Bavarians dominated the city around 1880, and 43% of second-generation Bavarians were still marrying from the same ethnic group and another 22% were married to someone from an adjacent region. Endogamy was even more prevalent among Prussians who were soon the largest German nationality in New York.

The neighborhood had its own clubs, lodges, theaters, athletic associations, bookshops, stores, restaurants and beer gardens. More than half of the bakers and carpenters in New York were of German origin, and many Germans also worked in construction. The German Lower East Side formed a trade junction between Europe and German-American traders who supplied goods to both rural and urban settlements in North America. There was a large German book market as well as a lively theater and music scene. Kleindeutschland had been a happy home to New York’s Germans.

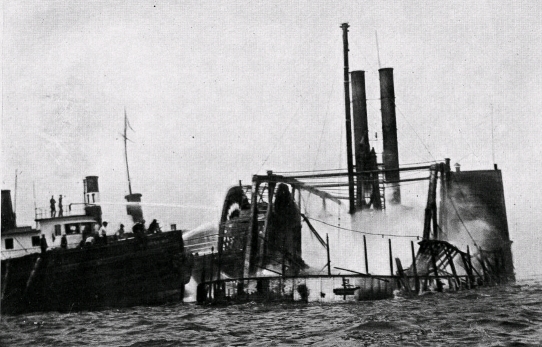

One of the deadliest peacetime maritime disasters in American history (and the worst one in New York’s history) would devastate their community when, on June 15, 1904, over 1,000 of them died when their steamship caught fire in New York’s East River. The General Slocum was a ship with a bad safety record and a history of bizarre accidents and untimely collisions.

St. Mark’s Lutheran church in Kleindeutschland organized an outing every year and chartered an excursion boat for a day of swimming, fun and food at a nearby recreation area, Locust Grove on Long Island Sound. 1,300 plus people boarded the General Slocum on this fine day. The band played as the happy passengers left the dock at 9:30 am, the music to include a typical mixture of German and American songs: Unser Kaiser Friedrich, America, Poet and Peasant, Bird of Passage, Waldvoeglein, Vienna Swallows, Swanee River, On The Beautiful Rhine, Dutch Patrol, Hip Hip Hurrah, Carousal, College, Ever or Never, Under The Double Eagle, The Picadore, Werner’s Parting Song, Children’s Carnival, Princess Pocahontas, Mrs. Sippi, Home Sweet Home. ‘Unser Kaiser Friedrich’ (the ‘Kaiser Friedrich Marsch’) was to be played again on the return voyage. It never had the chance.

The ship meandered up the East River. Just beyond East 90th Street, smoke was spotted billowing from below deck. A barrel of straw below had caught fire and, partly because the ship’s hoses were rotten, the crew failed to put out the fire, which within ten minutes became too big to handle. By the time they notified Captain William Van Schaick, it had become an inferno. Fearing an explosion if he dared dock near the many oil tankers along the East River piers, he decided to race at full speed to North Brother Island a mile ahead. Spectators on shore frantically shouted for him to dock the floating inferno, and the little boats following him watched in horror as the increased speed wildly fanned the flames which were also accelerated by the ship’s fresh paint.

As the fire spread over the whole ship, people had no choice but to leap overboard in a horrible scene of panicked, screaming people, some clinging to the side rails as long as they could before dropping into the murky water where whole families drowned. Only a few were rescued by nearby boats. Even though there were 3,000 lifejackets on board, they were all rotten and actually served to pull down those who wore them into the water.

The lifeboats could not be dislodged in time and would not have been able to be used anyway while the ship was speeding. When the blazing ship finally reached North Brother Island, the remaining passengers leaped off the ship, while nurses and patients from the island’s hospital rushed to offer help. Area boats picked up the living and the dead from the water in the wake of the ship, and the death toll stood at 1,021.

Thousands of family members and friends gathered at St. Mark’s Church anxiously waiting for word of survivors, while others raced to the pier designated as a temporary morgue. Some people lost their entire family in the tragedy, and funerals were held every hour for days on end in the churches of Kleindeutschland. Several people who lost their whole families committed suicide as a result.

The city held an investigation and Captain Van Schaick, executives of the Knickerbocker Steamboat Co., and the Inspector who certified the General Slocum were indicted within weeks. Captain Van Schaick was convicted of criminal negligence and manslaughter and sentenced to ten years hard labor in Sing Sing prison, but was pardoned after three years. He lived the rest of his life in seclusion. The Knickerbocker Steamship Company, however, escaped with only a nominal fine despite the fact that the company had falsified records regarding passenger safety.

Most survivors and their relatives departed from Kleindeutschland, unable to remain in a neighborhood so scarred by sadness and tragedy. By the 1910 census, only 10% of New York’s Germans still lived in Kleindeutschland. The Slocum tragedy all too soon faded from memory, replaced by the Triangle Shirtwaist factory as the city’s most notorious fire just seven years later, even though the Triangle fire’s death toll was only 148 people, 85% lower than the Slocum.

The onset of World War One quickly eradicated sympathy for anything German, including the innocent victims of the General Slocum fire, and the media no longer even mentioned it and rarely does today. By the 1920s, not many people had even heard about the General Slocum fire, and the Triangle fire still, even today, takes precedence in history books. All that was left of the Slocum tragedy was a small, annual memorial service at the Lutheran cemetery in Middle Village, Queens.

The Memorial to the victims of the tragedy in Tompkins Square Park says: “In memory of those who lost their lives in the disaster to the steamer General Slocum June XV MCMIV.”