Both the Strasser Familie singers from Laimach and the Rainer Familie brothers and sisters of Fügen began by travelling throughout Europe in the 1820’s performing traditional Tyrolean folk songs (Volkslieder) wearing their colorful trachten. They influenced notables such as Goethe and Beethoven (“Tiroler Lieder”), Rossini, Franz Liszt (variations on a Tyrolerlied) and others.

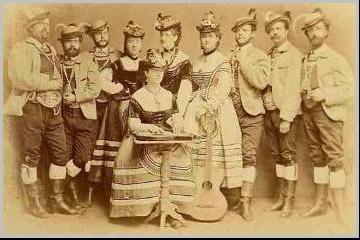

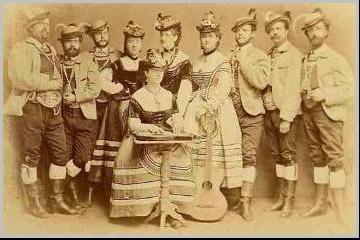

The Rainer Family was at first comprised of siblings Maria, Franz, Felix, Joseph and Anton Rainer who performed before English royalty in 1827 and Russian royalty in 1822. They toured through Bavaria, northern Germany and Sweden, singing for kings, princes are ordinary folk alike in palaces, theaters and concert halls. In 1827 they met in London, where they were given special favors from the Court, and as a result of their triumphant tour in London, their first song repertoire was printed and published. Above: the Family in 1873

After touring Europe they went to America: to New Orleans, St. Louis, Pittsburgh and Philadelphia, using New York as their base of operations from November of 1839 through January of 1840. Here, they studied English and arranged the next phase of their tour. In May 1843, they set off for home. Encouraged by their great success in the Americas, the Ludwig Rainer Society grew from five to up to fifteen singers and musicians by 1851.

Their travels took them again to England, where they sang before Queen Victoria, and then to Scotland and Ireland. In the following years, they concerted in Italy, then France, where Napoleon III received them in the Tuileries Palace, then Denmark, Sweden and Norway. In 1858, they came again to Russia and stayed for ten years, interrupted only by five brief visits home to attract new members. In the summer they played and sang in St. Petersburg and in winter in Moscow. Ludwig Rainer came with his group back to Austria in 1868, stayed in Vienna for six months and then traveled to Hungary, Transylvania, Wallachia and Turkey. Tired of traveling, he opened a hotel at home in 1870, taking only short tours until 1884. On his way to a wedding, he died in May of 1893.

The original Rainer Family Singers sang Franz Gruber’s little known carol “Silent Night!” in the parish church of Fügen in 1819 and in a performance at the Castle of Count Dönhoff on the occasion of a visit from Emperor Franz I of Austria and Czar Alexander I of Russia in 1822. They included the song on their tour of America. Thus, the first time “Silent Night!” was sung American soil was on Christmas Day of 1839 in New York City in front of the Alexander Hamilton Memorial in the cemetery of the Trinity Church at the end of Wall Street. It had to take place outside in front of the Hamilton Memorial in New York because Trinity Church, where their performances was scheduled, had been damaged by fire. It was a quarter of a century before it was published in English.

In 1834, the Strasser family first sang Silent Night in Leipzig, where they worked as glove vendors at the Christmas market. They were also a sensation, as was their performance of the carol, which was actually sung to attract customers to their ware. The publisher A.R. Friese of Dresden decided to publish some of the Strasser Family’s songs, including Silent Night, and it was immensely popular. Even the King of Prussia ordered it sung every Christmas Eve by his cathedral choir. When it was first printed around 1830, it was as a Tyrolean style song, however, and this version differed in many details from Gruber’s original composition because the singers had adapted it to their style, a folk style which helped make it so immortal.

Lied is a German art song for solo voice and piano. The earliest basic forms of lied come from the 15th century. In the 17th century, a new kind of lied arose, the general bass or continuo lied, mainly for upper classes and students, and they were simpler than the formal solo songs of other countries. After 1750, the lieder was set to folk type melodies with simple harmony and independent accompaniment. It was Schubert’s setting of Goethe’s Gretchen am Spinnrade (1814) and Erlkönig (1815) that first embodied the close identification with poet, scene, singer, and character, as well as the concentration of lyric, dramatic and graphic ideas into a single unit which characterize the finest 19th-century romantic lieder. Schubert’s 610 songs became personal and corresponding to nature and emotion. Wagner, Liszt, Schumann, Brahms and Strauss all cultivated the lied.

During the pre-Civil War period, a taste for the German lied crept into America, in part due to concerts by the likes of Jenny Lind, who introduced German song to American audiences. It spread even more rapidly because of Foster’s influence. After the Civil War, interest and admiration for German culture even more steadily increased and Liederkranz societies formed in nearly every city.

With the blossoming of interest in German music and international admiration of German culture at its height, many American composers went to Germany for study. They came home with a genuine appreciation and fresh approach to American popular music. German American singing groups sprang up all over America, preserving German musical tradition and keeping the culture alive. By the time a New York Sangerfest was held in Brooklyn, New York in 1900, over 6,000 singers from 174 German American singing societies flowed into the city. It was not until the Anti-German hysteria of World War One that America freed itself from the “bonds” of German music.

Stephen Foster’s songs are deeply associated with the Civil War. Not many people realize what an admirer of German music Foster was, or that he spoke German fluently and translated German songs into English and even cooperated with German composers, making their songs popular in America.

Stephen Foster was born in Lawrenceville, Pennsylvania on July 4, 1826, on the same day that John Adams and Thomas Jefferson died, the ninth child of a prosperous family. His father was a Pittsburgh businessman and politician, his brother a builder of the Pennsylvania canal system and the Pennsylvania Railroad, and his sister the wife of President James Buchanan’s brother. He was largely self-taught until he received some formal musical training from a friend, German Henry Kleber.

On a German piano purchased by Kleber, an accomplished musician who was also a merchant, performer, composer, impresario and teacher, Foster composed many great songs before he married Jane MacDowell and became a professional songwriter. Foster’s first hit was “Oh! Susanna.” His early minstrel songs became widely popular, and between 1850 and 1860 Foster wrote many of his best songs and most of their lyrics, including “Camptown Races,” “Old Folks at Home,” “Massa’s in de Cold Ground,” “My Old Kentucky Home,” “Jeanie with the Light Brown Hair,” and “Old Black Joe,” a total of 285 songs, hymns, arrangements, and instrumental works. His unhappy marriage led to several separations.

Although he was popular, Foster suffered great poverty, and combined with domestic problems, the death of his parents in 1855 and his journey into alcoholism, his life fell apart. From 1861, Foster lived alone in New York City, and in 1864 he died in the charity ward of Bellevue Hospital in New York City from complications after a fall from his bed. Shortly thereafter, his renamed publishing company, William A. Pond Co., published the last song he wrote a few days before his death, “Beautiful Dreamer.” During his lifetime he earned only $15,091.08 in royalties from his sheet music. He died with 38 cents in his pocket. He is probably the most underrated composer in history.

Kleber, an immigrant from Darmstadt, Germany, was quite well known in his own right and composed light operas popular in the era. He composed one especially for the great event of the first transatlantic cable being laid. Until the cable was laid, the fastest communication between Europe and North America took at least a week. The idea of a transatlantic cable was first proposed in 1845, and took years to complete. A massive project, it took Cyrus W. Field on the American side and Charles Bright and brothers John and Jacob Bretton on the British side of the Atlantic much hard work and financial maneuvering to do it.

The manufacture of the cable started in early 1857, and by the end of July it was stowed both on the American ship Niagara and the British ship Agamemnon. On August 5, 1858, after five attempts, both ships met and the two continents were joined. On August 16, communication was established with the message “Glory to God in the highest, and on earth, peace, good will to men.” But damage inflicted on the cable by the high voltages caused it to fail soon after and it took until July 27, 1866 for the final, successful, cable to be laid with virtually no problems. The first message sent on this, the final and successful cable, was: “A treaty of peace has been signed between Austria and Prussia.”

There were thousands of miles of undersea cables linking all parts of the world within 20 years. The original two cables stopped working in 1872 and 1877 but four other cables were in operation by then. It was not until the 1960’s that the first communication satellites offered a serious alternative.

Another of the many figures of the day who were steeped in German writers and German romanticism was Sidney Lanier. Lanier was born on February 3, 1842, in Macon, Georgia to a well-to-do family. He began playing the flute as a youngster, and his love of music continued throughout his life. He attended college, graduating first in his class shortly before the outbreak of the Civil War. At age 19, he enlisted in the Confederate infantry and served for almost four years, ending his experience in a Union prison in Maryland. Lanier’s health, which suffered in the War, worsened in prison and he struggled with tuberculosis until his death in 1881.

Shortly after the war, he taught school then moved to Montgomery, Alabama, where he clerked and was a church organist. He wrote his only novel, “Tiger Lilies” (1867) there before moving to Prattville where he taught and served as principal of a school. He married, moved back to his hometown, passed the Georgia bar and practiced as a lawyer for several years, during which time he wrote a number of poems in the “cracker” and “negro” dialects of his day about poor white and black farmers in the Reconstruction South.

He then moved to Baltimore and played flute for the Peabody Orchestra, becoming famous for a flute composition called “Black Birds,” which mimicked the birds’ song. He also wrote poetry for magazines, including his most famous works, “The Marshes of Glynn” (1878) and “Sunrise” (1881). Next, he became a lecturer and a faculty member at the Johns Hopkins University in Baltimore, specializing in the works of Shakespeare, Chaucer and the Anglo-Saxon poets. He published a series of lectures entitled “The English Novel” and a book entitled “The Science of English Verse” in which he developed a novel theory exploring the connections between musical notation and meter in poetry. In several of his poems, he attempts to find an equivalent for music in the written word. Only one of Lanier’s musical compositions was published during his lifetime, but recently, manuscripts have been made available.

To some outsiders, the refreshments were better than the art:

“It is generally conceded that the German Theatre evolved from a dilettante enthusiasm displayed at the German Vereins. In these social gatherings, private theatricals were given, and talent was eagerly sought for among the members. On Sundays, plays were preformed in the different Verein hall. It was a matter of art and beer, and even though the art might be bad, the beer was unfailingly good.”

from “The Life of Heinrich Conried” by Montrose J Moses, 1916

The general German population might have loved musicals and comedies, but they also appreciated Shakespeare, who had been popular in Germany from the eighteenth century. In fact, Shakespeare was performed more in the German-speaking countries that in the English-speaking countries!

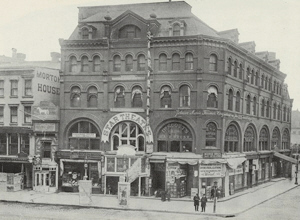

The “Star” or Wallack’s theatre on Broadway, below, was built in 1861. It was run by the Wallack family until 1881 and presented German language drama and opera. It was demolished in 1901.

|

O Psalmist of the weak, the strong,

O Troubadour of love and strife, Co-Litanist of right and wrong, Sole Hymner of the whole of life, I know not how, I care not why,

Yea, it forgives me all my sins,

|

|

| From Lanier’s “To Beethoven” |