He married Princess Charlotte of Belgium, daughter of King Leopold I, in the same year and they lived as Austrian regents in Milan until 1859. When Austria soon lost control of most Italian possessions, handsome young Maximilian and his pretty wife retired into private life at Trieste. There, in an enchanted corner of the Habsburg realm, he built the beautiful castle Miramar. His passion for ancient civilizations and botany inspired him to plan an expedition to the tropical forests of Brazil but fate had something else in store for him. He would become Emperor of Mexico.

Maximilian was tall, dignified, sincere and liberal in his social philosophy, and although he showed skill and courage militarily, he had a romantic nature with a love for the fine arts and a deep interest in and appreciation of other cultures. Armed with Maximilian’s profile, when Napoleon III sought to extend French imperial power, he and a conservative group of Mexicans schemed to crown the soft-spoken prince as “Emperor of Mexico,” and in 1859 they first approached him with the proposal.

This group of exiled hardline recruiters had been defeated in the bloody Reform War of 1857-60 which saw the triumph of liberal forces under Benito Juárez, a clever self-made, self-educated native from the Sierra of Oaxaca who was reportedly only 4 ft 6 inches tall. The Mexican liberals, led by the unprincipled and radical Juárez (who had the backing of the US), had seized power in 1860 and instigated a bloody anti-clerical policy wherein they confiscated the church’s money.

Juárez also suspended repayments on foreign debts, with the exception of those owed to the United States, an act inspiring the principal creditors of Britain, France and Spain to send a joint expeditionary force to occupy the port of Vera Cruz in December of 1861. Juarez repaid most of the outstanding interest and agreed to honor the debts, and Britain and Spain withdrew their claims, but France continued the war, marching inland and occupying Mexico City.

The exiled group under Napoleon III wanted their money back, but also wanted the Church and the big landowners, weakened by Juárez and his followers, to be restored to their state of dominance.

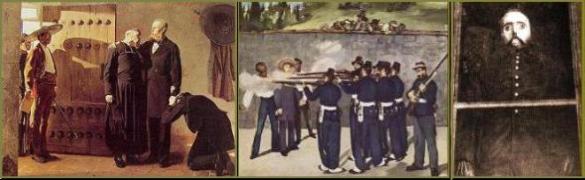

Their foremost representative was Yucatan lawyer José Maria Gutiérrez who went to see Maximilian in October, 1863 to lure him to Mexico to be the country’s “redeemer.” In May, 1863 French troops drove Juárez out of Mexico City and French commander General Forey convoked a puppet “Supreme Council” who issued a “spontaneous” call for Maximilian to come and rule Mexico. Gutiérrez and his associates deceived the gullible archduke by holding a fraudulent “plebiscite” in 1863 and using the results to convince Maximilian that the people desperately wanted him as king. Below: Napoleon III, Juarez and the delegation sent to entice Maximilian to be Emperor

The welfare of all his subjects was always his first concern. One of his first acts as Emperor was to restrict working hours and abolish child labor. He restored communal property, cancelled all debts over 10 pesos for peasants and forbade corporal punishment. He also decreed that peasants could no longer be “traded” for the price of their debt. He upheld Juarez’s land reforms, educated the Indians and the poor and extended voting rights to the common man. Maximilian even offered Juárez amnesty, and later the post of prime minister, but Juárez refused to accept either a government “imposed by foreigners,” or a monarchy. Undeterred, Maximilian built museums to preserve Mexico’s culture and the Empress held parties for the wealthy to raise money for the poor.

Chapultepec Castle was a residence for Mexican rulers dating back to the 14th Century when Nezahualcoyotl, the King of Texcoco, ordered a palace to be built at the foot of the hill. The Emperor hired several European architects to bring the castle up to a high degree of splendor and elegance. He hired expert botanists to plan the gardens, brought in furniture, antiquities and art and ordered construction of a straight boulevard connecting the Imperial residence with the city center, giving it grand appearance.

Meanwhile, in response to the French intervention and the elevation of Maximilian, Juárez sent General Plácido Vega y Daza to the US to gather Mexican American sympathy for Mexico’s “plight.”

As Maximilian and Carlota had no children, they adopted both grandsons of Agustín de Iturbide, who had briefly reigned as Emperor of Mexico in the 1820s. They gave young Agustín the title of “His Highness, the Prince of Iturbide” and intended to groom him as heir to the throne. Juárez was unimpressed by Maximilian’s agreeable policies, and refused to compromise or work with him, and when offered an amnesty if he would swear allegiance to the crown, Juárez refused. In desperation to end the fighting, Maximilian ordered all unrepentant captured followers of Juárez to be shot.

Maximilian was trying to put Mexico on the modern map and on a par with the other great nations, and he became as irritating to his former supporters as he was to Juárez. When papal representative arrived in Mexico and presented him with a 6-point memorandum which would abolish the reforms and give the Church back its privileges, Maximilian rejected the proposals, thus eroding support among the ultra-clericals. The French became prepared to withdraw once they realized that they had under-estimated Maximillian and could not easily control him. The Emperor was in trouble.

By the spring of 1865, Maximilian’s expensive social policies were under fire and the American Civil War had come to an end. US President Andrew Johnson wanted to shield the Western Hemisphere from European influences, leaving Juarez as the favored Mexican ‘candidate’ of the US government. Johnson invoked the Monroe Doctrine to give diplomatic recognition to Juárez’ government in exile and supply weapons and funding to his Republican forces.

The US ordered France to leave Mexico. When he could get no legitimate support in Congress, Johnson supposedly had the Army “lose” some supplies (including rifles) “near” (across) the border with Mexico (General Philip Sheridan wrote in his journal about how he “misplaced” 30,000 muskets close to Mexico). Johnson would not even meet with representatives of Maximilian. Napoleon III withdrew his troops in the face of U.S. opposition and Mexican resistance in 1866. The inevitability of Maximilian’s abdication was apparent to almost everyone but him. Maximilian, meanwhile, had welcomed immigrants to Mexico, including Confederates fleeing from the States at this time.

At this time, Maximilian’s wife Carlota journeyed to Europe to seek help from Napoleon III and even Pope Pius IX. On August 21, 1866, after she received formal notification that Napoleon lll would not comply with her request, she sent her husband a telegram in Spanish: “Todo es inutil” (all is useless). She left Paris a broken woman, and on August 23, 1866, after a long and jolting carriage ride over the mountains, she became ill. She arrived at her father’s old villa on Lake Como exhausted and confused and her doctor advised her to rest, but she did not.

On September 27, 1866, after another grueling trip, Carlota met with Pope Pius IX in Rome where she presented a draft stating how she needed his help to convince Napoleon lll to continue to support Maximilian in Mexico, but the Pope was unwilling to act at all. She had a complete mental breakdown and became convinced she had been poisoned by the French. She begged to be allowed to stay in the Vatican, which she visited daily, pleading in vain. She never went back to Mexico or regained her sanity.

Maximilian remained behind, refusing to abdicate and desert “his people” when the French pulled out of Mexico in March, 1867. Juarez and his army returned. Withdrawing to Querétaro in February 1867, Maximilian and his loyal followers sustained a siege for several weeks, until May 11 when they planned an attempted escape through enemy lines.

Colonel López, one of his closest aides, betrayed both Maximilian and the town, turning them over to the hands of the enemy. The city fell on May 15, 1867, and he was captured before he could carry out his escape. Two months later, Maximilian was condemned to death. European royalty and leading figures such as Garibaldi, the great Italian liberator and a hero to Juárez, sent telegrams and letters to Mexico pleading for Maximilian’s life, but they were in vain.

An embittered Juárez refused to commute the sentence and personally signed the death warrant. 35-year-old Maximilian and his loyal generals Miguel Miramón and Tomás Mejía died bravely before a firing squad on June 19, 1867. The Emperor spoke only in Spanish and gave his executioners a portion of gold not to shoot him in the head so that his mother could would not see her son’s face desecrated. His last words were: “I forgive everyone, and I ask everyone to forgive me. May my blood which is about to be shed, be for the good of the country. Viva Mexico, viva la independencia!” Some say he then mumbled: “Poor Carlota!” The first volley did not kill him, and he slumped to the ground in agony. The second volley did. The Juarista firing squad shot him in the eyes despite having taken the money. Below: Max’s death and his body

Supposedly, Maximilian collected some five million dollars in jewelry and gold coins, gold and silver plate and some bullion before his capture and had loyal aides hide it in 45 flour barrels loaded onto wagons with the instructions for the drivers to go to San Antonio and then to Galveston, Texas where it could be sent to Austria to Carlota.

A group referred to as “Maximilianos” left Mexico with the treasure but were killed by robbers before journey’s end, their bodies and wagons burned. The robbers could only carry so much, so they buried more of the treasure than they took with them, with the hopes of returning later. The group of robbers were later attacked and murdered by Indians and only one survived that knew the whereabouts of Maximilian’s treasure, and he later presented a treasure map of the location before he, too, died. The (mythical?) treasure is still buried to this day somewhere around Castle Gap, hidden high in the King Mountains north of El Paso, Texas.

Agustín de Iturbide y Green, 1863-1925, the “adopted” son, was born in Georgetown, Washington, D.C., the son of Emperor Agustin I’s second son Ángel de Iturbide y Huarte 1816 – 1872 and his American wife Alice Green. When Maximilian and Carlota took the throne, they invited the Iturbide family back to Mexico. Since Maximilian and Carlota could have no children together, they offered to adopt Iturbide y Green, and formally named Iturbide y Green their heir in 1865 with the title His Highness, Prince de Iturbide. With the overthrow of the monarchy, his biological family took him to England and then back to the United States. Iturbide y Green renounced his claim to the throne and title when he came of age. He returned to Mexico and served as an officer in the Mexican army. He was forced into exile after criticizing President Porfirio Díaz, and returned to Georgetown where he taught at Georgetown University for many years. He died in Washington, D.C

Don Salvador of Iturbide 1849-1895, son of His Highness Prince Salvador of Iturbide-Huarte and Her Highness, Princess Rosario of Marzán-Guisasola; Grandson of His Imperial Majesty, Austin I, and great-great-grandson of the Marquis of Altamira, was adopted by Maximilian in 1865. His adoptive mother, Carlota, sent him to Paris, where he lived until 1867 when he moved to Hungary. When living in the Austrian empire, he claimed from Franz Joseph a pension as his right as being an official son of Maximilian I. While living in Hungary, he married in 1871, and mingled with other petty royals, eventually moving to Venice where he lived in a rented palace. On a visit to Corsica, he died of a ruptured appendix. A rumor surfaced that Maximilian’s purported mistress, Concepción Sedano y Leguizano, 17, bore him a son.

Mexico experienced what was perhaps the longest period of suspension of payments on its foreign debt in modern history, spanning the period from 1828 to 1886.