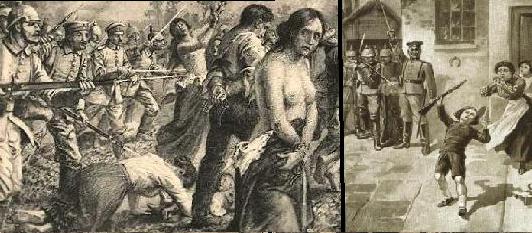

He judged them on their conduct in the crisis under consideration. This is the line that we all ought to take. Exactly as we admire the Germany of Korner and Andreas Hofer in its struggle against the tyranny of Napoleon’s France, so we should sternly condemn and act against the Prussianised Germany of the Hohenzollerns when it sins against humanity.Germany enticed Austria into beginning the war by encouraging her to play the part of a bully toward little Serbia. She began her own share of the war by the Belgian infamy, and she has piled infamy on infamy ever since. She brought Turkey into the war, and looked on with approval when her ally perpetrated on the Armenian and Syrian Christians cruelty worthy of Timur. She had practised with cold calculation every species of forbidden and abhorrent brutality, from the use of poison gas against soldiers to the use of conquered civilians as State slaves and the wholesale butchery of women and children. No civilised nation in any war for over a century has been guilty of a tithe of the barbarity which Germany has practised as a matter of cold policy in this contest. Her offences against the United States, including the repeated murder of American women and children, have been of the grossest character; and all upright far-sighted citizens of our country must rejoice that we have now declared that we shall take part in the war, both for the sake of bur own honour and for the sake of the international justice and fair dealing among the nations of mankind.

One of the chief of Mr. Raemaekers’ services has been his steady refusal to fog the issue by denouncing war or militarism in terms that would condemn equally a war of ruthless conquest. such as that waged by Germany against Belgium, and a war in defence of the fundamental rights of humanity, such as that waged by Belgium against Germany. Timid souls who lack the courage to stand up for the right; and utterly foolish souls who lack the vision to stand up for the right, and who yet feel ashamed not to go through the motions of doing so, find a ready and safe refuge in an empty denunciation of war. This is never objected to by the wrongdoer. On the contrary, it is in his interest; for to denounce war in terms that include those who war in defence of right is to show oneself the ally of those who do wrong. The Pacifists have been the most effective allies of the German Militarists. The whole professional Pacifist movement in the United States has been really a movement in the interest of the evil militarism of Germany. Raemaekers possessed too virile a nature, too high a scorn of all that is base and evil, to be guilty of such short-comings.

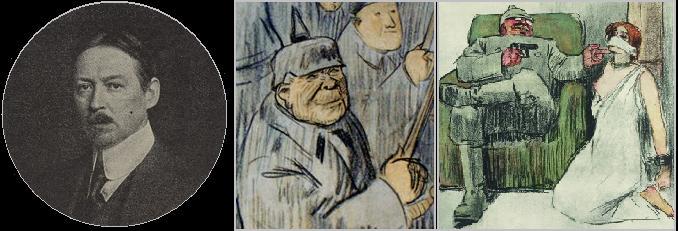

His soul flamed within him at the sight of the horrible evil wrought in Belgium by the German invasion. He was stirred to the depths by the knowledge seared into his soul that the worst manifestations of wrong-doing were due, not to the sporadic excitement of private soldiers who cast the shackles of discipline, but to the methodical, disciplined, coldly calculated, and ruthlessly executed designs of the German military authorities. With extraordinary vigour he has portrayed phase after phase of the evil they have done, sketching with a burning intensity of sympathy the sufferings of the women and children. He has left a record which will last for many centuries, which, mayhap, will last as long as the written record of the crime it illustrates. He draws evil with the rugged strength of Hogarth and in the same spirit of vehement protest and anger.

The prospect of a fat, steady paycheck enticed a myriad of illustrators to put their talents to work for war, and many Raemaekers clones also sprouted up, all diligently working at forming a new visual image of Germans which provokes immediate loathing.

When he arrived in Manhattan in 1917 to propagandize and work for Hearst papers, Raemaekers said quietly: “It would be better – I know it is impossible, but still it would be better – if all the Germans could be wiped off the face of the earth.”

The years between two wars showed in Raemaekers’ charcoal stick, if not in his words. Where once he drew blood, desolation, barbed wire, ravished women, a demoniacal Kaiser, he now pictured the forces of the world in abstract, often obvious, images. Churchill was a bluff skipper, Stalin a leering Satan, Hitler a skeleton, the U. S. Isolationist something like a village idiot. A devout Roman Catholic, Raemaekers seemed increasingly preoccupied with the lonely, grave figure of Jesus wandering through the world.

Louis Raemaekers lives modestly in Manhattan with a few of his possessions. He had sent to the U. S. some 600 cartoons – he contributed about 350 a year to the Amsterdam Telegraaf – forwarded for safekeeping to Herbert Hoover’s war library at Stanford University. For two months during the summer Raemaekers drew a cartoon a week for the New York Herald Tribune. Now he works for the afternoon tabloid PM. During World War I, Raemaekers made two cartoons a day, saw his work blown up in posters as big as 15 by 20 yards, was so powerful that he could portray his employer, Mr. Hearst, as an evil-looking dispenser of “seedition” (sowing seeds marked “cowardice” and “treason”). An obvious likeness of Hearst, although it did not bear his name, the cartoon appeared in Hearstpapers. Last week Louis Raemaekers hoped to shape U. S. opinion in World War II as he had in World War I. (End)