Before hostilities even erupted, the British public had already been subjected to a decade of an intense pro-war propaganda campaign which whipped up war fever by breeding hatred toward Germany. British supremacist Rudyard Kipling was one of the leaders of the pack. In 1914, he along with other respected writers such as Arthur Conan Doyle, John Masefield, William Archer, John Galsworthy, Thomas Hardy and H. G. Wells were secretly summoned by Charles Masterman of the War Propaganda Bureau to discuss ways of further promoting Britain’s interests during the war. Some of the men involved paid a high personal price for their war-mongering efforts later. When Arthur Conan Doyle wrote the pamphlet, “To Arms!” in 1914, it was arranged for 55-year-old Doyle to go the Western Front, and he served as a private throughout the war. Doyle wrote several other war books. His son, Kingsley Conan Doyle, joined the British Army, and on being wounded at the Somme then died after developing pneumonia.

Rudyard Kipling whipped the British public into a frenzy of Germanophobia with his vitriolic pro-war propaganda. Kipling encouraged his only son John to enlist even though the boy suffered from very poor eyesight. When his application was rejected on medical grounds, his father then pulled some strings, and John became a Second Lieutenant in the Second Battalion of the Irish Guards. 18-year-old Second Lieutenant John Kipling was one of 20,000 British soldiers killed on September 27, 1915 at the Battle of Loos. He was shot in the mouth and laid in a shell crater by a sergeant. A grieving Rudyard Kipling wrote: “If any ask us why we died, Tell them because our fathers lied.” When Kipling received the telegram saying that John was missing in action, he and his wife made countless journeys to France, searching for news on him, eventually concluding he must indeed be dead.

In 1915, the American public was firmly against becoming involved in a foreign war. That wouldn’t last too long. Soon enough, the war mongers were at their devilish best instigating, deceiving and lying, and the boys, some only 14 or 15 years old, were sent to die... by the million.

While the bogus ‘Bryce report’ of German atrocities was being concocted in Britain, British forces were no angels. They carried out air raids of their own on German cities, used poison gas in battles on the Western Front and executed two German nurses (in circumstances similar to those of Edith Cavell, condemned as a spy by the Germans). The greatest atrocity of the war was the Royal Navy’s inhumane trade blockade of Germany which caused hundreds of thousands of German civilians to starve to death. It met little public censure.

Manfred von Richthofen loved risks. He once climbed a church steeple and tied a kerchief to its lighting rod. He was a calvary officer from a wealthy Junker family with a riding and hunting tradition when the war broke out. He saw duty on both the Eastern and Western fronts as an Army scout. On May of 1915, he asked to be transferred to the Flying service. Richthofen recorded his first aerial combat victory on September 17, 1916. By the time his short life was over, he’d shot down eighty Allied aircraft and was the shining star of the air war. His red Fokker and graceful maneuvers became infamous to the enemy and made him a folk hero at home.

He spoke at the end of the terrible human cost of the war, and the personal responsibility he felt in taking so many lives. On April 21, 1918, his career ended when he was shot down over enemy lines. His opponents gave him a hero’s funeral, photo below.

John McCrae was a Canadian physician who fought on the Western Front in 1914 before being transferred to the medical corps and assigned to a hospital in France. He died of pneumonia while on active duty in 1918 at 46 years old. His volume of poetry, ‘In Flanders Fields and Other Poems,’ was published in 1919. McCrae apparently didn’t feel the same misgivings about war as the Red Baron and urges future generations to continue the fight in the original version of his famous poem:

|

Take up our quarrel with the foe:

To you from failing hands we throw The torch; be yours to hold it high. If ye break faith with us who die We shall not sleep, though poppies grow In Flanders fields. |

’Shropshire lad’ Wilfred Owen began to write at the age of 17. A devout Christian who spent a year assisting a minister before going to France to teach English, in 1915, Owen enlisted in the Artists’ Rifles before receiving his officer’s commission with a Manchester Regiment in 1916. After training, he was sent to France where he saw a lot of action, being sent back from the front with shell shock. Again in August 1918, he returned to France and earned the Military Cross before dying. Germany had its poets as well, although none are spoken of. But even the lowly foot soldier could be poignant.

“Nothing is so trying as a continuous, terrific barrage such as we experienced in this battle, especially the intense English fire during my second night at the front. Darkness alternates with light as bright as day. The earth trembles and shakes like a jelly..and those men who are still in the front line hear nothing but the drum-fire, the groaning of wounded comrades, the screaming of fallen horses, the wild beating of their own hearts, hour after hour, night after night. Even during the short respite granted them their exhausted brains are haunted in the weird stillness by recollection of unlimited suffering. They have no way of escape, nothing is left them but ghastly memories and resigned anticipation... ”Haven’t you got a bullet for me, Comrades?” cried a Corporal who had one leg torn off and one arm shattered by a shell – and we could do nothing for him... The battlefield is really nothing but one vast cemetery.” German Private Gerhard Gurtier, August 10, 1917, written on the receiving end of the Allied barrage at the Battle of Passchendaele four days before he was killed.

Then there were the critics. 21-year-old Vera Brittain was an undergraduate student at Somerville College, Oxford. Brittain interrupted her studies to enlist as a volunteer nurse when war broke out, nursing casualties in England and on the Western Front. For four years she witnessed the horrors of war first hand, and also experienced the loss of her fiance, her brother, and two close friends. She wrote ‘Testament of Youth,’ a powerfully written memoir which was published in 1933. Brittain became an influential pacifist in WW2.

She led a campaign against the RAF terror-bombing of German civilians under Arthur Harris. In 1944, she published ‘Seed of Chaos: What Mass Bombing Really Means’ and overnight she became a target of vicious smear tactics and media hatred and abuse. The publication received little attention in England but it provoked strong condemnation from President Roosevelt and savage criticism from the media, especially from George Orwell.

Before antibiotics were discovered, minor injuries could prove fatal. The Americans recorded that 44% of casualties that developed gangrene died. The Germans recorded that 12% of leg wounds and 23% of arm wounds resulted in death, mostly from infection. 50% of those with head injuries died and only 1% of those wounded in the abdomen survived. 75% of the wounds inflicted during the war came from shell fire, resulting in more traumatic injury than a gunshot wound. A shell fragment introduced debris making it more susceptible to infection. The shelling also produced tremendous psychological damage. Men would often suffer debilitating shell shock from enduring long bombardment. It was a misunderstood condition at the time, and some of its victims were executed as traitors. In Military Executions of the war, the British executed 346 of their own Commonwealth and British soldiers, most suffering from shell-shock, for alleged desertion and cowardice during the war, the French executed 600 of their own and the Germans 48.

About 8 million men surrendered, generally in large units, and were held in POW camps during World War One. All nations pledged to follow the Hague Convention on fair treatment of prisoners of war, and as a general course did so. The Camp conditions were satisfactory and actually much better than in World War II, thanks in part to the efforts of the International Red Cross and inspections by neutral nations. Germany held 2.5 million prisoners, Russia held 2.9 million, Britain and France held about 720,000 and the U.S. held 48,000. In Russian camps, starvation was most common for prisoners and about 15-20% of their captives died. Comparatively, in Germany, where food was also in desperately short supply, only 5% died. The war was the biggest factor in the spread the deadly “Spanish influenza” virus which resulted in the deaths of millions of people worldwide.

2,000,000 German soldiers were dead and 100,000 were missing and presumed dead. An astonishing 4,814,557 were wounded and another 14,673,940 suffered from illnesses. 60% of soldiers in the field had to be replaced because of injury or illness at every stage of war and the German army lost about one third of its men each year, so the replacement soldiers got younger as the war progressed until 85% of eligible German males were mobilized at some part of the war. The war changed every aspect of German society, from gender hierarchy to education, health care, and even the family structure and the discipline of children. From 9 to 14 percent of Germany’s pre-war population was killed or wounded in the conflict, with millions of others indirectly lost to starvation from the hunger blockade and food shortages, or from influenza and other epidemics.

|

| The Red Baron |

|

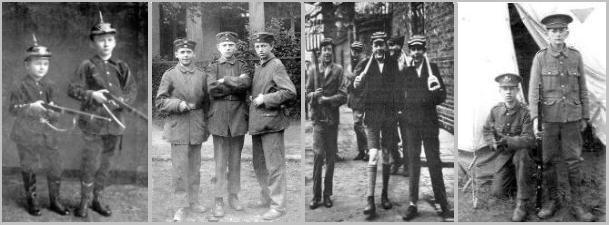

| Many soldiers on all sides were boys, some as young as 14. |

|

|

The Blue Max

War Dogs Poison Gas |

The Germans came back from war to a country thrown into political chaos, wracked by poverty and starvation. The British hunger blockade which killed thousands of German civilians continued even after armistice. The “peace terms” of the Versailles Treaty drove the country further into confusion at a time when the people were already suffering and grieving. Twice as many German soldiers were killed as soldiers of the British Empire. |

|

| One-armed, one legged, one-eyed men, blind men, men without full noses or mouths or only half a face begged for food. They came home with indelible mental scars as well, some as barely functional half-humans with shell shock or battle fatigue called “the shivers.” |

When the last surviving German army veteran of World War I was recently reported to have died in Hanover at age 107, there was no official confirmation available because Germany keeps no official records on its veterans from either world war! This event, when it was a soldier from the USA, Britain or France, resulted in headlines, ceremonies and numerous articles. Yet, even the German army’s Military Research Institute, which studies German military history of the 20th century, was “unable to provide information” about Germany’s last living veteran of World War One. A spokesman for the institute said. “Any form of commemoration of military events is seen as problematic here,” he said. “Our veterans only take part in public ceremonies when they are invited abroad to join commemorative events with veterans from other countries. World War I is seen as part of a historical line that led to World War II. You can’t equate the two but there is much debate about it.” Ah, “debate” again. Thus, those who bravely served their nation received no honorable remembrance.