Munich fell under the control of the Habsburgs twice in the 18th century. Ludwig I, of Bavaria was the third Wittelsbach who charted Munich’s destiny by having his architects design grand public buildings. In the 19th century, Munich reached its greatest heights of growth and development, and for the first time Protestants were allowed to become citizens. Duke Wilhelm V created the famous Hofbrauhaus for brewing brown beer in 1589, and in 1810, when Crown Prince Ludwig of the Wittelsbach family was to be married, a two week wedding reception party was held as a celebration. This party was so popular that it became a local tradition, the Oktoberfest.

Ludwig I was born in German Strasburg in 1786 and was king of Bavaria from 1825 to 1848. A great patron of the arts, and responsible for many neoclassical buildings in Munich and also encouraged industry. He initiated the Ludwig Canal between the Main River and the Danube, and in 1835, the first German railway was constructed in his domain.

Ludwig supported the Greek fight for independence, and his second son Otto was elected king of Greece in 1832 (one of his first acts was to ensure there was a brewery established in Greece and to this day Greece has good beer). After the 1830 revolution in France, Ludwig’s policies became more repressive, and he had a scandalous affair with dancer Lola Montez. He abdicated in 1848 in favor of his son Maximilian II, 1811-1864, king of Bavaria from 1848 until 1864.

Maximilian II of Bavaria, 36 years old, had married 19-year-old Protestant Princess Marie of Prussia. He was an intellectual, kindly man of good taste and saw the need for a moderate constitutional government. He was hampered by constant ill health.

Maxilian’s two sons, Ludwig II and Otto 1 of Bavaria were both mentally dysfunctional. From upon his older brother’s death in 1886, Otto I was King of Bavaria until 1913. However, he never truly ruled as King and was declared insane in 1875. He was confined under medical supervision until his death. Otto’s uncle, Prince Luitpold of Bavaria, served as Prince Regent for Otto until his own death when his son Ludwig became the next Prince Regent and he eventually deposed his cousin Otto and received the title of Ludwig III. Otto was permitted to retain his title as a formality, so Bavaria technically had two kings until Otto’s death in 1916.

His brother, Ludwig Friedrich Wilhelm, Ludwig II, otherwise known as the Mad King of Bavaria, the Swan King, the Recluse of the Alps or the Dream King, is best known for his home, grandiose Neuschwanstein castle. Born as the oldest son of King Maximilian II of Bavaria 1845, he spent much of his early life in the ancient castle of Hohenschwangau and was given a thorough education.

From childhood, he showed special interest in architecture and art. Ludwig grew up admiring Louis XIV of France, but had no real practical knowledge of government affairs or kingly responsibilities. The life of the eccentric ruler who became king at age 19 is a legend. At the age of 15, Ludwig attended a theater performance of ‘Lohengrin.’ He was deeply affected by this legend and identified with this lonely knight. One of his first acts as King was to summon Richard Wagner to Munich and this rescued Wagner from a serious financial crisis. Over the next few years, Ludwig loaned the composer vast sums of money.

After their first meeting Ludwig had written Wagner: “I want to lift the medial burden of everyday life off your shoulders for ever. I want to enable you to enjoy the peace you so long for so that you will be able to unfurl the mighty pinions of your genius unhindered and in the pure ether of your rapturous art! Unknowingly you were the sole source of my joy from my earliest boyhood, my friend who spoke to my heart as no other could, my best mentor and teacher.”

|

|

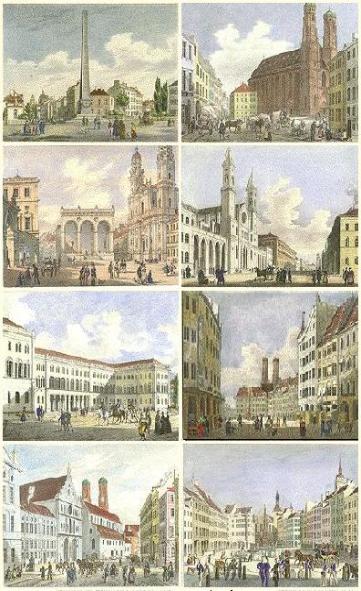

| Left: The Mad King, his Castle and his musician. Right: Old Munich. Below: The dead king | |

|

|

The festival theater planned for Munich was built instead in Bayreuth and inaugurated in 1876 with the cycle “Der Ring des Nibelungen.” In 1882, “Parsifal” was premiered here. Without Ludwig’s commitment, there would never have been a Bayreuth Festival. But because the king had no real fortune, his patronage of Wagner had to be financed from tricky financial maneuvering which caused contention among Ludwig’s cabinet officials.

Ludwig was not pleased with Bismarck’s drive for a unified Germany in 1870 as he was worried about the diminished role Bavaria would play in such a confederation. Ludwig was already gradually withdrawing from society and the upsetting politics of the day filled with trends he didn’t approve of. He maintained close relationships with only select people and relatives, and his engagement to his cousin Sophie was cancelled in 1867. He communicated with his government only through messengers and by telegrams.

He travelled to France in disguise to get ideas for his new palace projects, and by around 1880 his only real passion was for his ever expanding castles of Neuschwanstein and Herrenchiemsee. On November 12, 1880, Wagner conducted a private performance of the ‘Parsifal’ prelude for Ludwig. This was their last meeting.

Ludwig’s outrageous spending, his demands on the treasury and nationalistic stand against Prussia caused the government to declare him insane and placed him under house arrest. On June 13, 1886, the king and his psychiatrist Dr. Bernhard von Gudden, were found in Lake Starnberg where they had presumably drowned, giving birth to various rumors and theories.

Ludwig was not disliked by his people. He kept them out of war, and the construction of his famous fairy-tale castles on his own private property employed a lot of ordinary people and brought a considerable flow of money to the regions involved, sort of a “mad king public works program.”

They liked his eccentricities, such as him travelling “incognito” among his people and surprising those who were “unknowingly” hospitable to him later with lavish gifts!

In 1950, it was officially closed. Various sections were destroyed or filled in during later highway work, and parts of it were lost in recent times when the new marvel, the Main-Danube Canal, was constructed. A lovely monument was once in a park like setting by the lazy banks of the Kanal and is one of a mere 10% of German monuments that managed to survive the massive Allied bombing. It is now all but hidden under a highway overpass near Erlangen and difficult for people to see or visit.

A rebellion broke out in November of 1705 in the district of Burghausen led by Sebastian Plinganser, Johann Georg Meindl and an army of 3,000 peasants, craftsmen and burghers. Armed only with farm implements and scythes, they marched upon Munich to protest against the Austrian regime and clashed with Bavarian troops loyal to Austrian occupation forces under General Kriechbaum in an event remembered as the Sendlinger Mordweihnacht (Sendling Christmas Massacre).

Early Christmas morning, a short distance away from Munich’s city walls near the hamlet of Sendling, the soldiers opened fire and left an estimated 3,000 dead or wounded peasants and farmers. Those who survived sought refuge in a nearby church but were rounded up and executed. Some 682 of them were buried in mass graves. Kriechbaum then proceeded toward Lower Bavaria. On January 8, 1706 near Vilshofen, the remaining rebel force was annihilated.

The town of Braunau am Inn played an important role in the uprising. It hosted a provisional Bavarian Parliament (often seen as the precursor of the modern Bavarian parliament) headed by Plinganser on December 21, 1705 (the “Braunauer Parlament”). The congress was formed for the defence of Bavaria and comprised of representatives of the four estates: aristocracy, clergy, burghers and peasants. Later, after Maximilian II Emanuel, Elector of Bavaria, was banished, he reorganized himself as defender of Bavaria with a large army and summoned the Braunau Parliament. In 1715, when he was finally able to evict the Austrians. Not only did these conflicts include countless deaths and growing discontent among the people, they imposed a national debt guessed to be around 32 million guilders on an already impoverished population.

Braunau am Inn was Bavarian until 1779 when it became an Austrian town under the terms of the treaty of Teschen, which settled the War of the Bavarian Succession. Again, between 1809 and 1816 it was a Bavarian town under the terms of the treaty of Bratislava. In 1816, Bavaria ceded the town to Austria after the Napoleonic Wars and it has remained Austrian since.

He discovered, among other things, 19 minerals, one of which carries the name Kobellite after him. Author of many scientific papers, he also published some modern specialized books.

Kobell was the curator of the mineralogical national collection and appointed as a member into the Academy of Sciences. He was a passionate hunter and mountain climber, and great lover of nature, happy to journey to the mountains and live among the local inhabitants, where he became an interpreter of their dialects. King Maximilian II often invited him to accompany him as a friend and fellow hunter. He also wrote numerous poems, narrations and plays. In his literary work, the epic poems and poetic narrations are told in the Bavarian dialect, and describe the everyday life of the hunters and farmers. He told stories in the Pfalz dialect as well which he learned from his grandfather. Von Kobell died in 1882.

Another native son was Ludwig Ganghofer, a much loved author of novels about the homeland. Born in 1855, after beginning his education in mechanical engineering, he ended up studying the history of literature and philosophy in Munich, Berlin and the University of Leipzig, where he received a doctorate. His first play was the highly successful “Der Herrgottschnitzer von Ammergau” (The Lord’s woodcarver of Ammergau) in 1880 in Munich. When it played in Berlin, it was a smash hit. Ganghofer worked as dramatic adviser, a freelance writer and editor until 1891 when he devoted his time to writing. He was a personal friend of Kaiser Wilhelm II, and worked as a correspondent during the First World War, writing strongly patriotic accounts of the war.

He returned to writing books at war’s end. His last book was “Das Land der Bayern in Farben-photographie” which was dedicated to King Ludwig III of Bavaria. Ganghofer’s work is still published today and popular for its simple, healthy Alpine themes. Kaufbeuren, his birthplace, is a 1,000 year-old free imperial city in the Bavarian Allgäu area. Its main landmark is the Five Buttons Tower, built in 1420. The narrow lanes, old walls and towers from the middle ages are still in place. Founded by a Frankish knight around the year 800, the town played host to the kings and emperors of the Middle Ages.

The München Siegestor was built by King Ludwig I in 1844-1852 in tribute to the Bavarian Army and modeled after the Constantine arch in Rome. In World War II, it was heavily damaged. Four fallen lions which once adorned the top are shown smashed, above right.

The oldest of the Wittelsbach palaces, The Residenz, dating from the 16th century was destroyed. The Munich University Institute and its entire collection was destroyed by Allied bombing. Munich’s oldest church, St. Peter’s Church from 1169, and the Cuvilliés Theatre at the Residenz, a grand theatre built for the Wittelsbach court between 1746 and 1777, were gone.

So was the Bavarian State Library, Bayerische Staatsbibliothek, one of the largest libraries in the German-speaking world, founded in 1558 by the Wittelsbach Duke Albrecht V. The last totally unnecessary cultural bombardment took place only few days before end of war. Approximately 6,500 residents of Munich were killed by the attacks, 300,000 were left homeless and it took two years to clear away the 5 million cubic meters of bomb rubble.