|

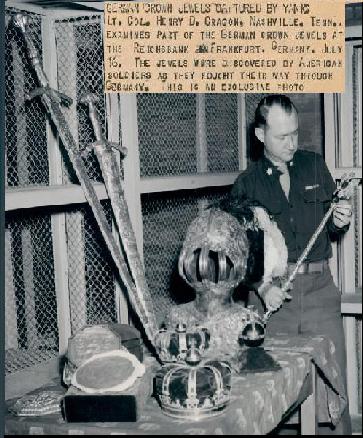

Germany’s entire cultural legacy was in the hands of its enemy. In the wire photo above an American officer examines “Germany’s crown jewels,” or at least a fragment thereof. Such treasures discovered in the Soviet zones were usually stolen and removed for all time. But many such objects found their way out of their homeland by means of Americans as well, both officially and unofficially. |

What occurred in old Aachen, a city blessed with rich architectural treasures in the heart of Germany, was typical. Only four out of hundreds of the city’s rarities were even somewhat spared Allied bomb destruction: the cathedral, the 14th century city gate, the Frankenberg Castle and the Haus Heusch. The remains of Charlemagne were hidden in the woods beforehand by Germans hoping to protect them. The occupying Americans later ordered a G.I. to go and bring his remains back, and the soldier supposedly asked upon his return with the sack of bones, “So, where do I dump this?”

The archives, library and treasures which could be moved had fortunately been taken out earlier in the war for safe keeping by German officials, and Charlemagne’s heavy coronation chair was intact, protected from English bombs inside a masonry shield, the floor beneath it reinforced by temporary brick arches and shoring. Not so lucky was the old Teutonic Knights castle at nearby Siersdorf where Americans set up a command post. They moved valuable medieval carved panelling from the Aachen Rathaus (city hall) which had been stored there for safety out into the weather, ruining it.

At Rimburg Castle, the furniture and artwork were scattered, vandalized and thrown into the moat, and the locked rooms broken into and rifled. When MFA&A advisers later toured, they concluded the destruction was a combined effort among the British, Canadian and American troops. There were slashed pictures and cases of books from the Aachen library broken open with their contents strewn about by souvenir hunters. The concern of MFA&A officials with the German collections being desecrated extended only to the fact that “looted Nazi art” might be included in the destruction, artwork which the Allies had pledged in advance to restore to the “rightful owners.”

There were thousands of Russian DPs in Aachen living in a huge barracks, and even though the camp was in a state of chaos, violence and filth, Allied troops issued passes every afternoon for a group of these DPs to visit the town. These visits turned into major looting expeditions. According to Allied military records, the DPs would leave the camp with empty baskets and briefcases and return at nightfall “loaded down like camels” with all sorts of goods, leaving murders, rapes, and robberies in their wake. With a few honorable exceptions, nobody cared. This occurred across Germany.

In order to accommodate the thousands of pieces of “Nazi plundered artworks,” U.S. occupation forces in 1945 established “collecting points” in German warehouses and office buildings, among them Marburg, Munich, Offenbach, and Wiesbaden. The Wiesbaden Collecting Point held artworks from German museums, artworks confiscated from German nationals, and other artworks subject to restitution to store and identify. Objects, German and otherwise, were retrieved and taken to one of the collecting points. The ‘Property Division of the Office of Military Government for Germany, U.S. Zone Headquarters,’ administered the recovery and restitution efforts. Additionally, a MFA&A branch, with help from Allied military staff, began restitution of some objects to its country of origin or, at times, to the rightful owner... or at least who they guessed or were told was a “rightful owner.”

Capt. Walter Farmer was the Wiesbaden collecting point’s first director. The first shipment of artworks which arrived there included cases of antiquities, Egyptian art, Islamic artifacts, and paintings from the Kaiser Friedrich Museum. On November 6, 1945, Farmer was ordered by the U.S.Military to select at least 200 German museum-owned artworks and ship them to the USA for the National Gallery of Art in Washington, D.C. to hold on to in exchange for “wartime reparations” and as an “entitlement of the American people to view the masterpieces.” The U.S. military governor of Germany said the works would be returned only when Germany had “re-earned its right to be considered as a nation”; the U.S. Secretary of State announced that the art would “eventually be returned intact, except for such levies as may be made upon them to replace looted artistic or cultural property which has been destroyed or irreparably damaged.” Among the 202 paintings shipped were five van Eycks, four Titians, two Vermeers, five Botticellis and 15 Rembrandts.

Outraged, Farmer called this “blatant looting” and “systematic looting” of the Kaiser Friedrich Museum and the Berlin Nationalgalerie by the U.S. Army, and on November 7, 1945 wrote the “Wiesbaden Manifesto” which urged the MFA&A not to take part in the plan because it violated international law and “establishes a precedent which is neither morally tenable nor trustworthy.” Risking court-martial, twenty-four MFA&A officers signed the document. But the plan went through anyway. In November of 1945, under the code name “Westward Ho,” 202 paintings by Cranach, Raphael, Rembrandt and other great masters left Germany for New York City, and from 1946 to 1948 the art circulated throughout various American museums.

The so-called “restitution” process continued until 1949, at which time the US, believing most allegedly NS pilfered art had by then been restored to its rightful owners, turned the remaining museum collections over to the Treuhand Verwaltung fur Kulturgut, a West German trustee organization empowered to make any further restitution and disposition of the artworks. In 1962, what remained passed into the control of the Oberfinanzamt in Munich. Museum art collections in Germany continued to shrink, however, as the standards of proving ownership became less stringent and claims continued to pour in, a trend which continues to empty museums to this day.

The Allied directives were very broadly interpreted, leading to the destruction of thousands of paintings and sculptures, for example during the plundering of the `Haus der Deutschen Kunst in 1945 by American military authorities who confiscated its art and appointed themselves as art jurors. Col. Gordon W. Gilkey was in charge of locating and confiscating politically incorrect art and he and his cronies spent months methodically ferreting out what they deemed to be “miltaristic,” amassing an astonishing 9,000 pieces of condemned art.

These artworks included a series of pictures of the battles in Eastern Europe which had been commissioned by the National Socialist government, and because of that association, they were brought to America to prevent them from being exhibited in Germany after the war. The art was sent to the Alexandria, Virginia US Army Center of Military History. Some 200 works of art in this purloined collection were apparently not regarded as too “dangerous,” because they were spread out across the USA throughout the years and now hang in libraries and schools.

In 1982, some 6,000 of the works were finally returned to Germany and sent to the Bavarian Army Museum in Ingolstadt to be studied and catalogued, but were not available to outside researchers and remained in storage inaccessible to the general public! The U.S. Army War Art collection of the Department of Defense retained 800 or so works either by Hitler or “glorifying” Hitler or the Third Reich to “prevent a resurgence of National Socialism.” About 600 milder pieces similar to this group belong to the German Government today and are heavily protected in storage. In 1993, it was announced that part of this collection would be shown to the public when it was moved to Berlin, but a storm of protest prevented this from occurring. It seems it is regarded as degenerate art. We will probably never know, for we will probably never be allowed to judge for ourselves.

The worst part of this story is that the of the 9,000 works of art collected by our zealous art police, those which were not sent to the US or elsewhere but remained behind in Germany were considered “of no value” and destroyed. The US military, who had so rigorously denounced German censorship and ridiculed the concept of “degenerate art,” now acted as art critics and censors and left a trail of destruction in their wake. With knives, fires and hammers, they smashed countless sculptures and burned thousands of paintings, although a few pieces made it home to the USA to grace the living rooms and dens of the destroyers.

Thanks to their efforts, there is a blank chapter in art history, one purged clean of artists such as Arno Breker, Josef Thorak, Adolf Ziegler, Oskar Martin-Amorbach, Adolf Wissel, Julius Paul Junghanns, Udo Wendel, Karl Alexander Flügel, Albert Henrich, Michael Kiefer, Franz Xaver Wolf, Jürgen Wegener, Ivo Saliger, Walter Schmock and others, who, simply by virtue of their political ideologies or associations have been at best neglected and at worst, had all of their art from the war years destroyed during the “reeducatioin” of the Germans to good, American values.

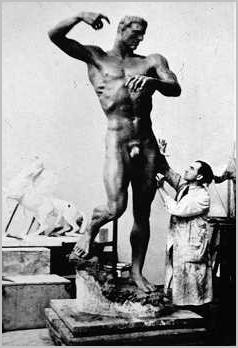

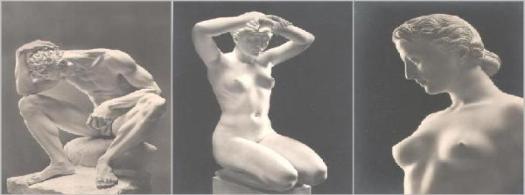

Most of his work was masterfully executed and neoclassical in nature. The proportions of his figures, their highly coloristic surfaces with vivid contrasts between dark and light accents and their strong musculatures made his work intensely dramatic. He was acclaimed worldwide as a great master. For his 40th birthday in 1940, the German government gave him a country house just east of Berlin known as the Jackelsbruch estate which had been built in the 18th century for Friedrich the Great. He lived here with his Greek wife. Breker was a prolific artist and amassed a considerable fortune. Until Germany’s defeat, Breker was a highly respected professor of visual arts in Berlin. Deemed politically incorrect, tragically 90% of Breker’s work was destroyed after the war.

In 1945, Breker and his wife fled to the Alps in search of safety and some of his works were loaded onto a truck to Bavaria. He left his Jäckelsbruch studio along with its comprehensive collection of international art, including bronzes by Rodin and works done by abstract artists, in the hands of a pupil. Soon, however, his three studios in Berlin, Jäckelsbruch and Wriezen were taken over by Allied troops who confiscated everything they found, destroying much of it first in a fit of vandalism. Ultimately, communist East Germany confiscated all of Breker’s property and land. While nearly all of his sculptures had survived the bombings, more than 90% of his work was destroyed by the Allies after the war, the private works as a result of looting and the public works as a result of intentional destruction by the Allied military authorities during “re-education.”

Breker was summoned in the Fall of 1945 and questioned by the US military, but it was not until 1948 that Breker was officially ‘denazified’ in a court proceeding. Like millions of other Germans, Breker was ultimately classified as a ‘fellow traveler,’ a category that allowed him to work again, but for which he was fined 100 marks, a sum that Breker refused to pay. The court then offered him an alternative punishment: building a fountain for the city of Donauwörth, which Breker also declined. They also demanded that he publicly express his ‘regret’ at having accepted official commissions from the National Socialist regime, but this, too, Breker refuses to comply with, saying it is an “undemocratic and undignified extortion” of the defeated. No more was heard of the matter.

He returned to Düsseldorf where for a time he worked as an architect. However, he also received some private commissions for sculptures and produced many portrait sculptures. In 1970, he was commissioned by the king of Morocco to create work for the United Nations Building in Casablanca, but this work was destroyed. Breker in life, and even after death, was subjected to “backlashes,” including controversy in Paris where some of his works were exhibited in 1981. In the same year, anti-Breker demonstrations accompanied an exhibition in Berlin. Even in 2006, a group of German leftists gathered to protest near an the House of Arts in Schwerin where an exhibition of 70 works owned by Breker’s widow was being held. They entered the exhibit, wrapped up every sculpture of the exhibit with toilet papers or paper-rolls, deeming it a “fascist” exhibition and demanding it be closed down, but the Curator of the House of Arts refused to be intimidated.

Even after German reunification in 1990, his land and property were neither returned to him, nor was he reimbursed for it. The works which he had exhibited in Paris and left behind were also confiscated and auctioned off in the early 1960s. Because of a 1947 Allied occupation law, German citizens were prohibited from buying them. However, Breker, with help from a Swiss friend, was able to buy back a few of the irreplaceable pieces which had been expropriated from him. One rescued figure was missing its arms which had been expertly sawed off by American or Russian soldiers and may exist today somewhere. Another work, a famous bust which was confiscated by French authorities in 1946 is thought to have suffered a similar fate. Breker’s last major work was a monumental sculpture of Alexander the Great intended to be located in Greece. He died in Düsseldorf in 1991.