The beautiful Baroque castle Schloss Moritzburg was built from 1542-1546 as a hunting lodge for Duke Moritz of Saxony and later remodelled as a pleasure seat with formal park for August the Strong by the architects Matthäus Daniel Pöppelmann and Longeloune. When Soviet troops were closing in during the last days of World War Two, the royal family hid some treasures to prevent them from being looted by Soviet troops.

Part of the treasure remained hidden for more than half a century until a German postman found some of it with a metal detector. It was reclaimed by the royal family who later sold a good part of the lot at auction, including a gold and silver gilt jewel casket made in 1701 for Augustus the Strong. The family treasures were only a fraction of the collection of the royal house of Saxony, as most of the buried collection was found by the Soviet authorities after the estate forester was forced to reveal where it had been hidden. Only three crates were buried elsewhere and escaped detection, these objects being part of them. The proceeds of the sale were used to finance the family’s return to new communist-free Saxony.

The Teacup in a TempestThe Saxon State Library began in Dresden 440 years ago first under the auspices of Saxony’s ruling nobility and then to administrators and scholars who carefully selected and purchased the collection. Since Saxony had become one of the most powerful territorial states in German by the mid-16th century, many books were collected by Elector Augustus, 1553-1585, and included manuscripts from the middle ages and also those pertaining to local industry and the professional trades, many of which were uniformly bound by Dresden bookbinders in 1556. By the end of World War II, the Saxon State Library had 2,384 surviving incunabula. Today more than half of these are in Russia.

In the summer of 1999, over 5,100 predominantly manuscript music scores (including a major part of the Bach family archive) once stolen by a Ukrainian trophy brigade from the Sing-Akademie in Berlin were discovered in Kyiv. A cantata by Carl Philip Emanuel Bach which not been heard in 225 years since its initial premiere in 1785 was among them. Rare printed books and correspondence files from the collection are still missing, and as yet no trace of them have been found.

In 2007, European gold jewellery from between the 5th and 8th centuries A.D. went on show in Moscow for the first time since it was seized by the Red Army from a Berlin museum in 1945. In May and June, 1945, Red Army soldiers plundered three boxes with 1,538 artifacts of jewellery and other objects from the Merovingian era that a Berlin museum had hidden for safety in a bunker in Berlin to protect them from bombing. These are objects from the era of Germanic kings from 482 to 714, an era that has yielded fewer artifacts than any other in European history, such as a German 7th-century iron sword sheath from Sigmaringen-Gutenstein.

700 items of the 1,300 which emerged from their dingy hiding place to be displayed were stolen from Germany. Russia calls the looted trophy art “art stored in conditions of war.” What was modern Germany’s reaction? At the same time the Russian officials were crudely reiterating their official refusal to return cultural loot to Germany, the German Culture Minister attended the official opening and said the exhibition marks “a special event in German-Russian cultural relations” and loaned more than 200 objects to complement the show whose exhibition catalogue was printed in Germany!

In a nauseating display of arrogance, spite, greed... and violation of the Hague Convention, Poland has stubbornly clung to one of its looted German treasures. For decades, Germany has asked Poland to return a vast, priceless collection of original German manuscripts of writing and music once part of the Prussian Library collection which form an integral part of German history. The treasure was hidden in castles and monasteries for safety during the war, mostly in the Benedictine Abbey and its two churches in the German city of Grussau in Silesia, which at the time was still part of Germany.

The collections were found, taken as loot and stored at Jagiellonian University in Krakow since the end of the war. The tens of thousands of documents, now re-named the “Berlinka Collection” by Poland, include composer Robert Schumann’s archives, a letter written by Martin Luther in 1530; a decree signed by Louis XIV dated 1664 and even some correspondence from George Washington. The collection also contains original works of such world-famous German writers and composers as Goethe, Schiller, Bach, Beethoven and Mozart, all a crucial part of German history and culture. In this blatantly criminal theft, Poland has been obdurate in its refusal to show good will and do the right thing. Poland feels that they deserve it in return for wartime damage done to Poland by Germany, despite having already received a huge, free chunk of Germany at war’s end, including thousands of German businesses, mines, factories, homes (furnished down to the smallest child’s toy left behind by expelled civilians) and hundreds of intact medieval cities now passed off as part of THEIR cultural legacy, as well as parks, railroads, highways, bridges, forests, rivers, bridges and lakes.

As World War Two was drawing to a close in 1945, the US Army arrived and briefly occupied sleepy Quedlinburg, one of the lucky hamlets spared destruction by bombing. Twelve of the most precious treasures disappeared, but before an investigation could commence, Quedlinburg was turned over to the Red Army.

In 1983, rumors surfaced which led to an investigation by a German agency dedicated to recovering looted national treasures. The trail led to the State of Texas and to an oddball thief by the name of Joe Tom Meador, once a forward observer for an artillery unit and one of many men who made an advanced art out of thievery during their service in Germany. Although two of the works are still unaccounted for, Germany, managed to buy back the treasures for an outrageous price of 3 million dollars from Meador’s estate. This scene has been often repeated through the years.

Castles were gravely damaged. In the Rhineland, Rimburg Castle’s furniture and artwork was scattered, broken and thrown into the moat, and the locked rooms broken into and rifled. There were slashed pictures, and cases of books from the Aachen library broken open and their contents strewn about by souvenir hunters. At Augustusburg in Bruehl, Allied troops bivouacked in the bomb damaged castle and caused even more destruction. Police had no authority over (or incentive) to control US soldiers who continued to go in and out, looting as they pleased. Two Durer portraits were stolen from the Castle Schwarzburg, which were returned later only after a court battle. The castle Schloß Rurich near Hückelhoven dating in part from the 13th century survived the immense destruction caused by “Operation Queen” on November 16, 1944 which laid waste to several nearby towns and cities only to be hit by a grenade attack on Christmas of 1944, which caused immense, and in part irreparable damage. The valuable castle library of over 18,000 volumes was thoroughly looted by American GIs.

The family treasures of the duchy of Hessen were stored for safe keeping at the palace of Kronberg. In 1945, the US army confiscated the palace for use as an Officer’s Club and they discovered the treasures hidden in the cellar and parceled them out. Some went to the US and some were sold to Switzerland. In 1946, the theft was discovered but it was too late.

Treasures of the House of Hesse The American Protectors & German War ArtBritish troops stole the jewels of the Duke of Mecklenburg from the palace Gluckenburg in 1945. They also broke open the Sarcophagi in the palace crypt, throwing aside the mummies while rooting for valuables. Palaces in Schleswig Holstein and Buckeburg lost their treasures and antique furniture, which British troops sent home to Britain. It was not only the foot soldier who looted. British General Staff Field Marshall Sir Alan Brook personally removed valuable books and artwork from the Potsdam library of Cecilienhof. His partners in this crime included none other than the Duke of Cummingham, fleet admiral of the Royal Navy, and Sir Charles Portal, the Marshall of the Royal Air Force who so zealously crusaded for the total destruction of Germany by bombing.

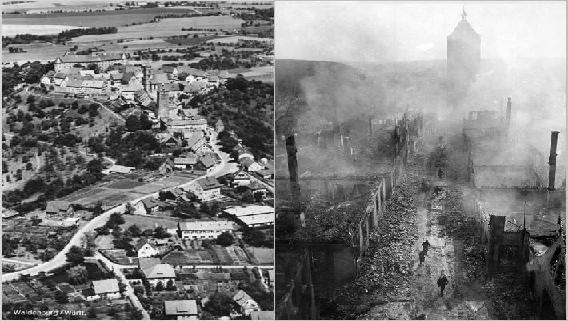

Waldenburg in Baden-Württemberg was first mentioned as the home of a castle, a fief of the noble family Hohenlohe, in the year 1253, and it was designated as a city in 1330. In the 16th century, the old castle was converted into a residence of the Prince of the Dukes of Württemberg. In the 19th Century, it was extensively renovated by a line of Hohenlohe-Waldenburg. By 1944, the city of Stuttgart, decided to move its impressive art collection at the Staatsgalerie of Baden-Württemberg, to a safer location. Never dreaming a sleepy old castle would be a target of Allied bombs, they sent many of the treasures to the tiny hilltop town of Waldenburg, 40 miles away. It is said that the citizens of Waldenburg formed a human chain to carefully transport the books and artworks, one at a time, up the steep hill to the castle, shown in the photo before and after 1945, below.

The city of Stuttgart was indeed absolutely levelled by Allied bombing, and in April 1945, on the flimsy pretext that “Nazis were hiding in Waldenburg,” Allied forces pounded the hilltop until the little village and ancient castle were almost totally destroyed by American artillery units. One version of the story goes that “homeless and desperate villagers burned anything they could find in order to stay warm, including the treasures” (the same villagers who made a tremendous effort to get the objects to safety a short time earlier). The other version is that it was thrown into one of numerous bonfires lit by Allied soldiers in the aftermath of their carnage. In any case, after the war, curators assumed that the entire collection was burned. A bound collection of 53 prints showing Augsburg nobles in various states of ornate dress and armor called the “Augsburger Geschlechterbuch” was among the evacuated treasures presumed lost. Created in the first part of the 16th century, it was a very important artifact.

|

| Waldenburg |

|

|

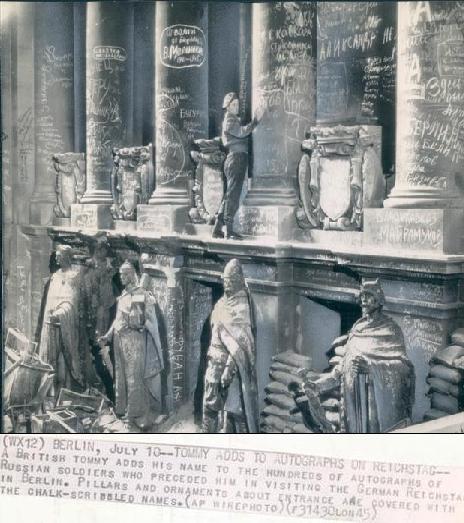

| Graffiti & 1945 US soldiers empty an Austrian palace of what they considered looted art. |

Throughout Germany, priceless art, religious and secular treasures, were violently torn from church-altars, wretched from museum walls or even stolen from private collections and homes by Allied soldiers. The coffins of Schiller and Goethe were looted by US soldiers who took six of Goethe’s medals. While officially America and Britain were not “seizing” any artwork as war booty, whole squads of Allied thieves were busy personally “liberating” rare books, illuminated manuscripts, gold and silver religious objects, sculpture and paintings as well as bullying German civilians into forking over their few valuables.

The “Salzburg of the Kapuzinerberg,” a 1565 woodcut, was one the oldest portraits of Salzburg. During the bombings, it was hidden for safety in a salt mine nearby. In 1945, soldiers of the US Forces in Austria (USFA) overtook the guarding and restitution of art, and during their watch countless valuables were stolen, including this priceless work of art. It has never been recovered.

US troops in Salzburg and Upper Austria under US. General Harry Collins, 42nd US division stole various art treasures from Austria, including a Salzburg gold coin collection hidden in Hallein. Seven valuable paintings including a Rubens and a van Dyck, and seven valuable prints, including four Dürers, were stolen from the salt main of Alt-Aussee while under supervision of US personal with the full knowledge of the Allied authorities. Members of the 83st US infantry division plundered St. Florian Monastery in Austria in 1945, freely taking paintings, antique furniture and Celtic gold treasure which they removed with 5 army trucks.

Six and a half tons of gold worth over seven million dollars in 1945 was recovered from Ribbentrop’s castle ‘Schloss Fuschl’ near Salzburg and turned over to the US Army on June 15, 1945. It totally disappeared and there are no records of it being received at the Frankfurt US Foreign Exchange Depository. Much of the gold “recovered” by the Americans was re-smelted, hence erasing any and all identification marks and numbers.

In the same manner by which panels painted by Albrecht Dürer ended up in Brooklyn and a manuscript of Friedrich the Great’s was brought to the USA by an American G.I., millions of rare books, artworks and other treasures were pilfered, some by means other than theft. The thousands of cameras, antique swords, knives and antique guns which German civilians were required to surrender at war’s end ended up in the states, usually with a bogus provenance. On internet auction sites today, there are pages and pages of “souvenirs” lifted or extorted from pitiful victims of the war by Allied soldiers, even toys, family bibles and photographs.

On a tip that 7 miniature 16th-century paintings stolen from Germany by American GIs at the end of the War were resold in the USA, the German government asked for their return. The new “owner” refused and instead engaged Germany in a protracted legal battle. He was a museum curator who claims he bought them “thinking they were reproductions.”

In the “confusion” of the last days of the War, as forces of the 66th U.S. Infantry Reserve and the 71st U.S. Infantry Divisions occupied bombed out Pirmasens, paintings belonging to the town which had been stored in the air-raid shelter during the war were stolen sometime in March of 1945, while the townspeople were burying their dead. In the year 2003, through the American FBI’s Art Theft Program, three of the fifty paintings by the German painter Heinrich Bürkel were recovered and have since been returned to their rightful owner, the Pirmasens City Museum. But this is rare.

Some loot found its way home. A lovely Baroque ivory figure crafted by Balthasar Permoser in 1700 depicting Omphale and Hercules was last seen on a train-load of art headed for “safekeeping” in Kassel in March 1945. It turned up in 2006 at Sotheby’s auctions in New York, via a collector in California. After proving its provenance, it was returned to Berlin’s Museum of Decorative Arts. US army personnel also stole three original writings from Martin Luther which were found and returned in 1996. A rare manuscript of Robert Schumann was found at an auction in London in the 1990s. 200 famous paintings taken from the Kaiser-Fridrich-Museum in Berlin by American soldiers had to be returned in March 1948 under public pressure.

It wasn’t just the American foot soldier who looted, either. US officers stole an original writing of Aristotle, a Gutenberg bible and 250 original letters to Erasmus of Rotterdam from the University library in Leipzig before turning the city over to the communists. Even US High Commissioner Lucius D. Clay tried to confiscate the stamp collection of the Reich Post Museum for the US but his plan was rebuffed by the higher courts. Eight of the most valuable stamps of the collection, however, were taken.

Das Hildebrandslied is the oldest heroic poem in German literature and the only surviving example in German of its genre. The codex itself was written in the first quarter of the 9th century. The codex was looted by a US army officer in 1945 and sold to a book dealer. It was discovered in California and returned to Germany in 1955, but in greatly damaged condition. The first sheet, which had been cut out and disfigured to avoid identification, wasn’t found until 1972 in Philadelphia. The manuscript is now home, in the Murhardsche Bibliothek in Kassel.The real estate and whole households of the millions of expelled ethnic Germans provided loot for years to come in those areas. The German books, including some rare manuscripts, banned by the Soviets and Allies alike during ‘re-education,’ while generally burned, often vanished with no accountability. Not only was there was unbridled theft of German patents, copyrights, music, research data, scientific and educational studies, there was massive, unjustified requisitioning of German-owned property in just about every part of the world, often done on the flimsiest of pretexts.

In some areas of eastern Europe where ethnic German property was stolen, there have been some attempts to compensate. In Romania, 90 percent of 128,000 attempts at claiming back confiscated property have failed to produce results so far, but there is progress:

Chivalry is not dead. In Bulgaria, former monarch Simeon Saxe-Coburg, who fled his homeland as a child in 1946 after communists took over, returned from exile to his home. He became prime minister from 2001 to 2005. Bulgarian law now allows restitution of nationalized royal property. In 1991, Hungary became the first post-communist country in the region to pass laws on partial compensation for expropriated property. There were 817,811 claims submitted for compensation of property taken away during communism by 2005. In the Czech Republic, having German blood makes it nearly impossible to reclaim one’s rightful property, and it has only very rarely taken place. Poland is the only post-communist country in the region that has not passed a restitution or compensation law.Another lucrative plunder was scientific. At the end of World War II, both Allied and Soviet scientific intelligence experts accompanied the invading forces into Germany to plunder as much equipment and expertise as possible from the rubble, and they were delighted and shocked at the advanced German technical achievements they found.

Discovered Marvels “Project Paperclip”German cultural institutions recently issued a catalogue (2008) detailing thousands of objects of art that disappeared from Berlin at the end of the war in the hope that foreign governments will return the stolen art to them. Over 180,000 items disappeared from itemized and inventoried German collections alone along with thousands of other cultural treasures which have never been recovered.

Lastly, at this point in time, many individuals whose families had willingly sold artwork even before the war and were paid for that work are today suing for art supposedly looted by Nazis, claiming that their families must have been “under duress.” It has evolved into nothing more than a lucrative racket for some, and is emptying German and Austrian museums of what precious little art they have left. To make matters worse, Germany has paid dearly in compensation for art actually pilfered by the Soviets or destroyed by the Allies in bombing runs.